Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in adults

Leukaemia in adults affects more than 6,000 people in Spain every year. Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia is the most prevalent type of leukaemia in the paediatric population but it also affects some adults.

The information provided on www.fcarreras.org is intended to support, not replace, the relationship that exists between patients/visitors to this website and their physician.

Information provided by Dr. Josep Maria Ribera, Haematologist and Senior Consultant of the Haematology Service of the Catalan Institute of Oncology – Badalona. Researcher at the Josep Carreras Leukaemia Research Institute. Professor of Medicine at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. (Barcelona Medical Association Co. 14049)

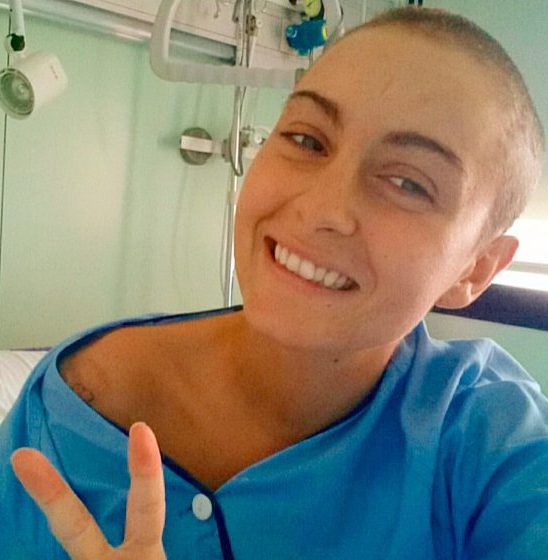

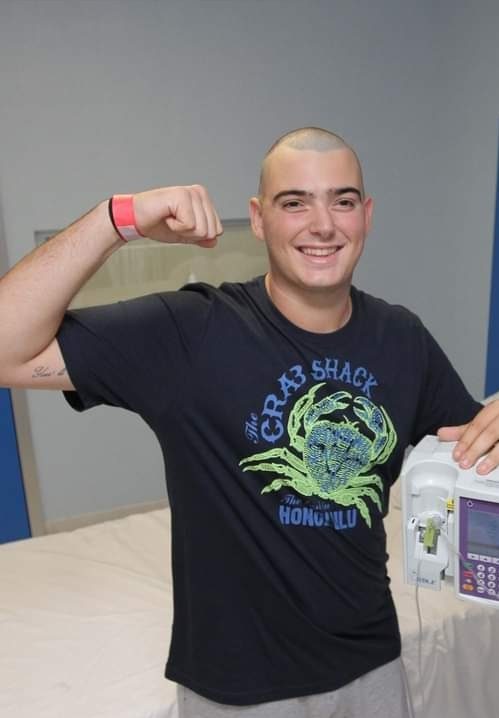

Ares

Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia.

“When I

was 26 years old I was diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia with

Philadelphia+ chromosome. This type of leukemia always requires a bone marrow

transplant. I was very lucky because the Josep Carreras Foundation found me a

100% compatible donor. I will never be able to thank my donor in person for her

selfless act that saved my life. My donor lost nothing by doing it and I gained

EVERYTHING: being here, breathing, getting up every morning and seeing the

faces of my family and friends, LIVE, something that seems so simple but for

many people it is not.”

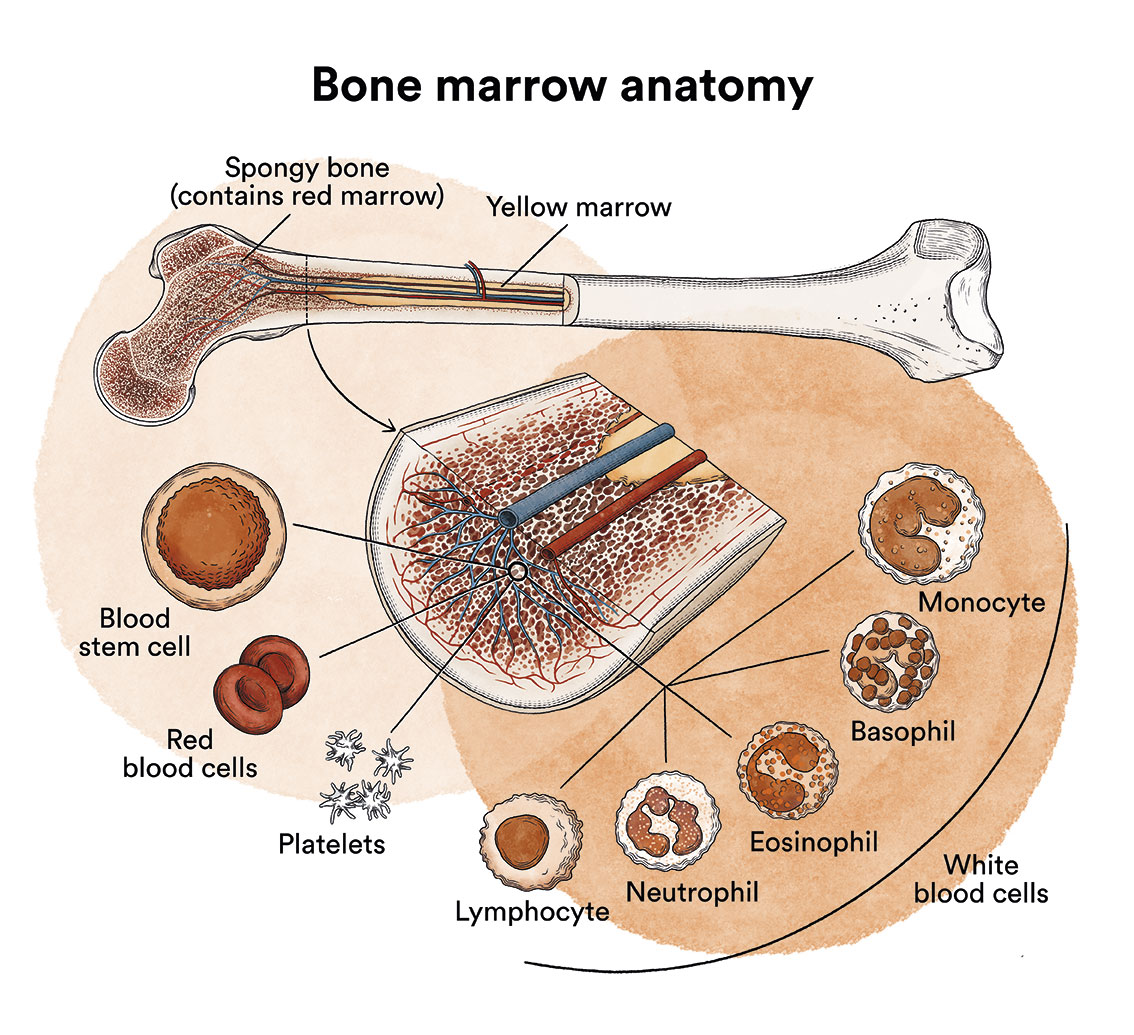

Leukaemia is a type of blood cell and bone marrow cancer.

See section Leukaemia, bone marrow and blood cells.

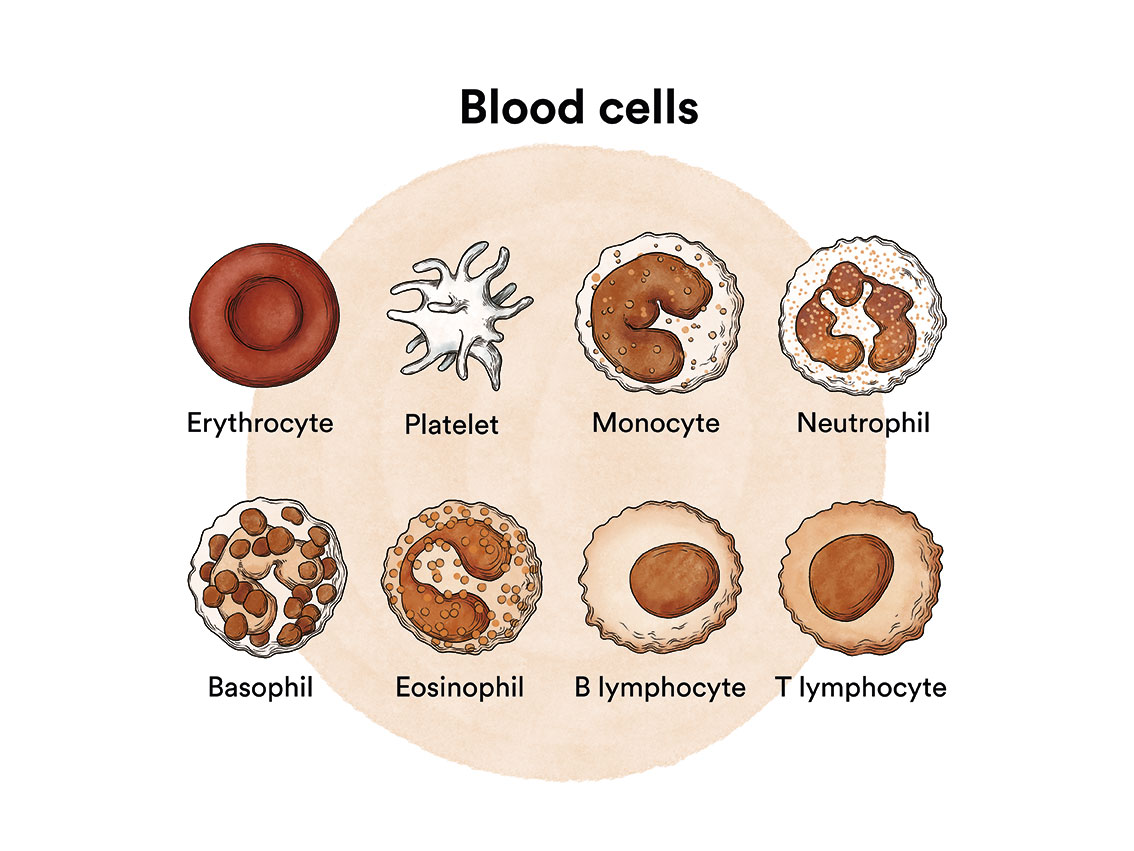

Acute leukaemias are a group of neoplastic diseases characterised by a malignant transformation and uncontrolled production of immature haematopoietic cells of the lymphoid (acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, ALL) or myeloid (acute myeloblastic or acute myeloid leukaemia, AML) lineage.

Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia is a type of blood cancer in which, for unknown reasons, excessive numbers of immature lymphocytes (lymphoblasts) are produced. Cancer cells multiply rapidly and crowd out normal cells in the bone marrow (see Leukaemia, bone marrow and blood cells), the soft tissue in the centre of bones where blood cells are formed.

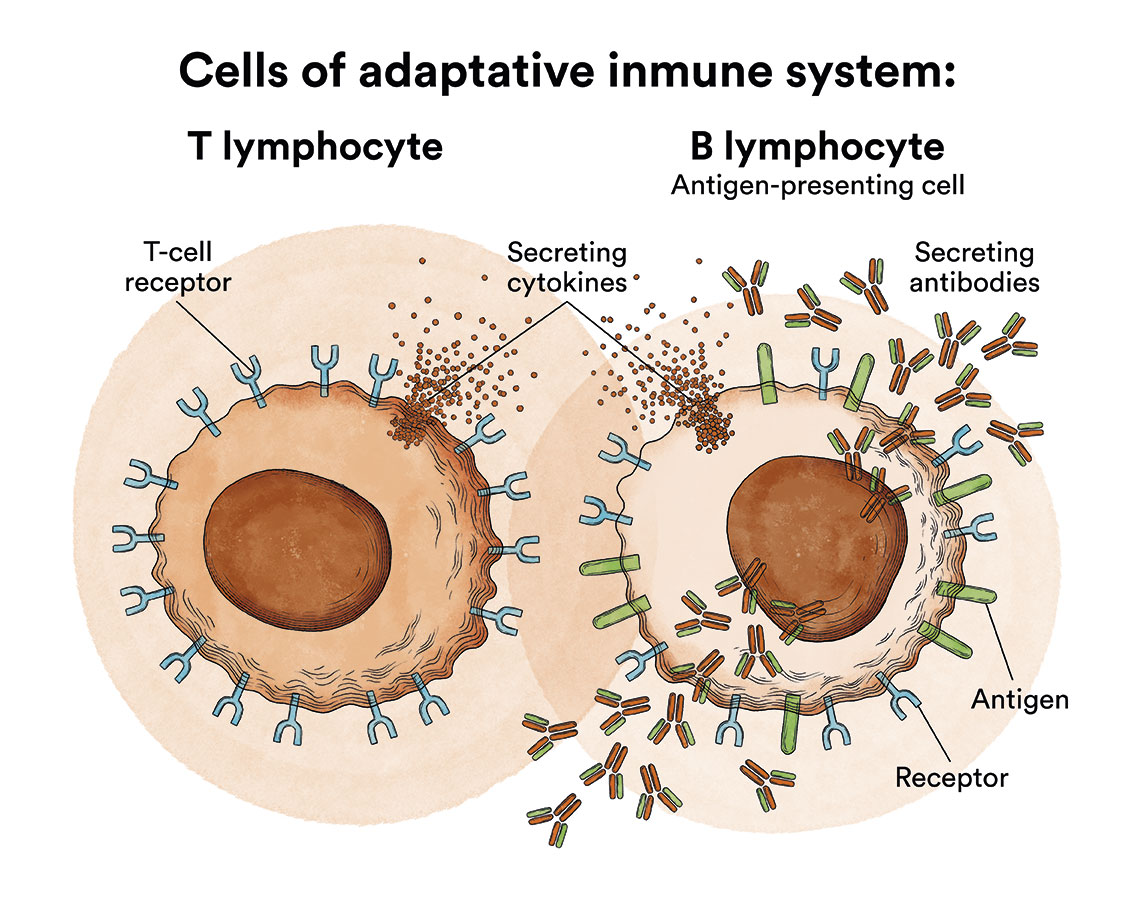

Under normal conditions, lymphocytes are produced in the bone marrow and in other organs of the lymphatic system (thymus, lymph nodes, spleen), and are responsible for our defence as they are able to attack, directly or through the production of substances called antibodies, any invading agent or abnormal cell that occurs in our organism. In ALL, lymphoblasts (lymphocyte precursors) are produced in excessive numbers and do not mature. These immature lymphocytes invade the blood, bone marrow and lymphoid tissues, causing them to swell and increase their normal size. They can also invade other organs, such as the testicles or the central nervous system.

Although acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) predominantly affects children (it accounts for 80% of leukaemias in the paediatric population), it is not uncommon to see it in adolescents and young adults. In adults, this type of leukaemia predominantly affects young males (average age 25-30 years). Only 10-15% of patients are over 50 years of age. In Spain, the annual incidence of ALL in adults is 30 new cases per million inhabitants per year. In total, around 1,400 people are diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in Spain every year.

Although acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) predominantly affects children (it accounts for 80% of leukaemias in the paediatric population), it is not uncommon to see it in adolescents and young adults. In adults, this type of leukaemia predominantly affects young males (average age 25-30 years). Only 10-15% of patients are over 50 years of age. In Spain, the annual incidence of ALL in adults is 30 new cases per million inhabitants per year. In total, around 1,400 people are diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in Spain every year.

Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia can affect B-lymphocytes, which produce antibodies to help fight infection, or T-lymphocytes, which are responsible for coordinating the cell-mediated immune response.

The types of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia are therefore divided into: B-acute lymphoblastic leukaemia and T-acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (less common). Therefore, the World Health Organization classifies ALL according to the type of lymphocyte affected (B or T) and the degree of maturation of the lymphocyte, differentiating between:

– B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (includes several subtypes identifiable by immunophenotypic studies, referred to as Pro-B, common Pre-B, Pre-B and mature B or Burkitt-like)

– T-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (includes several subtypes identifiable by immunophenotypic studies, referred to as Pro-T, Pre-T, cortical thymic and mature thymic)

Chromosomal translocations (displacement of part of a chromosome to another chromosome) and alterations in certain genes that vary the prognosis and treatment of the disease can be detected in all of them. For example, the presence of the so-called Philadelphia chromosome, a translocation between chromosomes 9 and 22 [t(9;22)], confers a particularly poor prognosis to this variety of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, requiring a different treatment than for other ALL.

The specific causes of most cases of adult acute lymphoblastic leukaemia are not known. There are also some risk factors that are associated with a higher likelihood of developing a type of leukaemia. A risk factor is anything that increases the likelihood that a person will develop cancer.

Risk factors associated with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia are, according to the American Society of Clinical Oncology:

- Genetic disorders. Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia occurs most commonly in people with the following inherited disorders:

- Down Syndrome

- Ataxia-telangiectasia

- Li-Fraumeni syndrome

- Klinefelter’s syndrome

- Fanconi anaemia

- Bloom syndrome

- Neurofibromatosis

- High radiation doses. People who have been exposed to high levels of radiation (see Leukaemia, bone marrow and blood cells) may be more likely to develop acute leukaemia (myeloid or lymphoid). This includes people who have received radiotherapy for another cancer or long-term survivors of atomic bomb or radioactive leak accidents. Electromagnetic fields generated by high-voltage power lines have not been shown to cause acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Mobile phone use is not a known risk factor for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia.

- Chemotherapy. People who have received chemotherapy for another cancer may develop acute myeloid leukaemia related to previous therapy.

- Chemicals. Prolonged contact with benzene-containing products (found in petroleum, cigarette smoke and some industrial workplaces) increases the risk of acute myeloid leukaemia. However, exposure to industrial solvents and hair dyes has not been shown to increase a person’s risk of developing leukaemia.

- Some viral infections. Human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1) infection can cause a rare type of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Most cases occur in Japan and the Caribbean area. In Africa, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) has been linked to Burkitt’s lymphoma, and also to a form of acute lymphoblastic (Burkitt-like) leukaemia.

Leukaemia, like other cancers, is not contagious. See section Leukaemia, bone marrow and blood cells.

The clinical manifestations of patients with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia reflect, on the one hand, a bone marrow failure, i.e. a lack of production of normal blood cells caused by the proliferation of lymphoblasts in the bone marrow and, on the other hand,the infiltration of the various organs and tissues by lymphoblasts. See section Leukaemia, bone marrow and blood cells. Onset is almost always acute and clinical manifestations usually precede diagnosis by no more than two months.

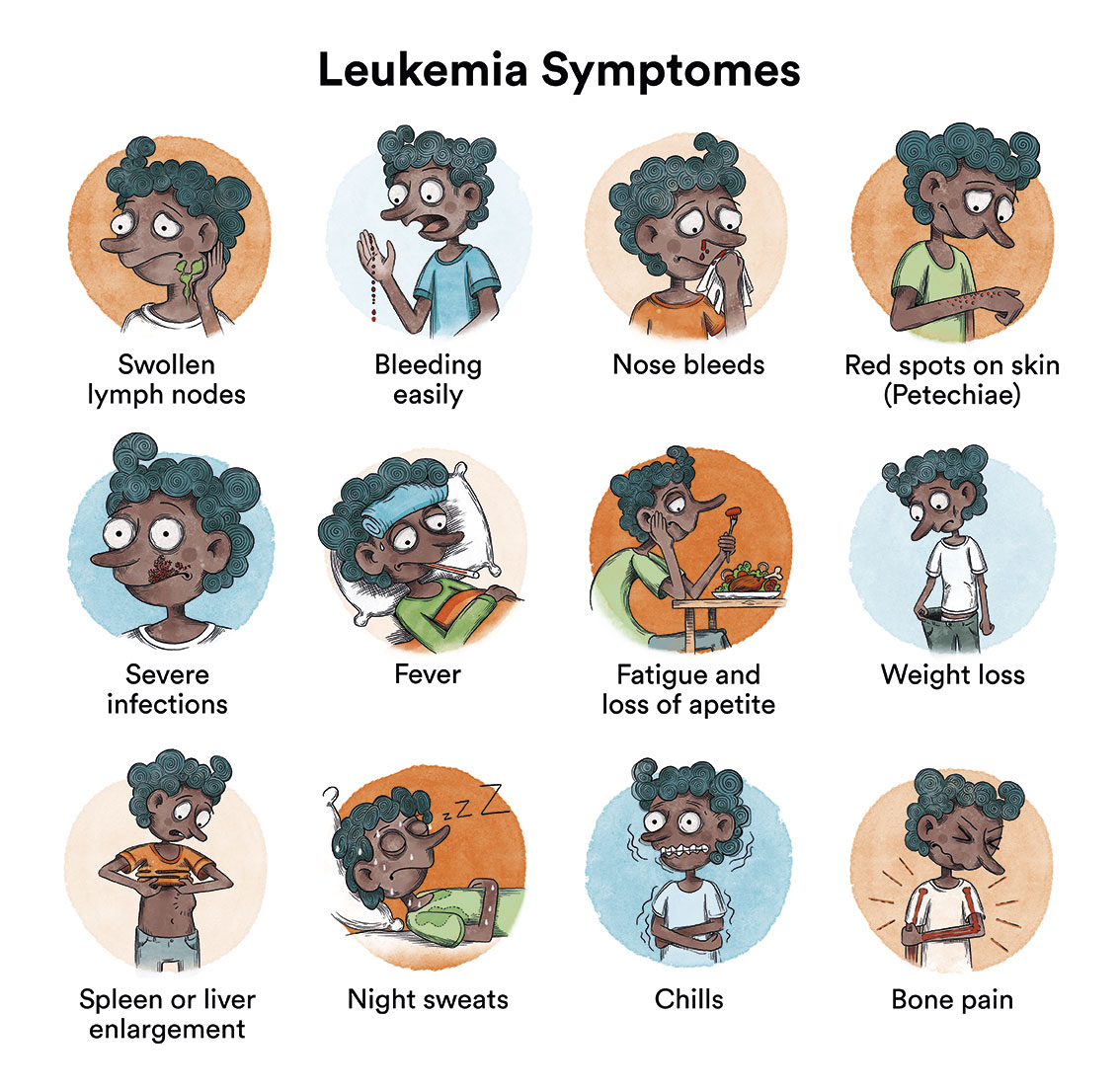

Typical symptoms include: loss of appetite, feeling of weakness and fatigue, fever, bone, joint and muscle pain, bruising of the arms and legs caused by a lack of platelets. Occasionally there is spontaneous bleeding (nose, gums) or excessive bleeding from small wounds.

Some patients may experience infections (abscesses, sinusitis, pneumonia, etc.) as initial symptoms. In others, enlarged lymph nodes and abdominal discomfort may be observed as a result of an enlargement of the liver and spleen. A small percentage of patients may present manifestations as a result of compression of neighbouring structures (e.g. those inside the thorax) by swollen lymph nodes, or symptoms resulting from infiltration of the central nervous system (headache, vomiting, drowsiness, etc.), testicles (pain, swelling) or bones (bone pain).

Although any organ can be infiltrated by lymphoblasts, the most frequently affected organs are the liver, spleen and lymph nodes. In children, the frequency of infiltration of these organs is 80 %, 70 % and 50 %, respectively, while it is somewhat lower in adults. Infiltration of other organs such as breasts, testicles, skin and mucous membranes is very rare at diagnosis, although it may be the initial site of relapse.

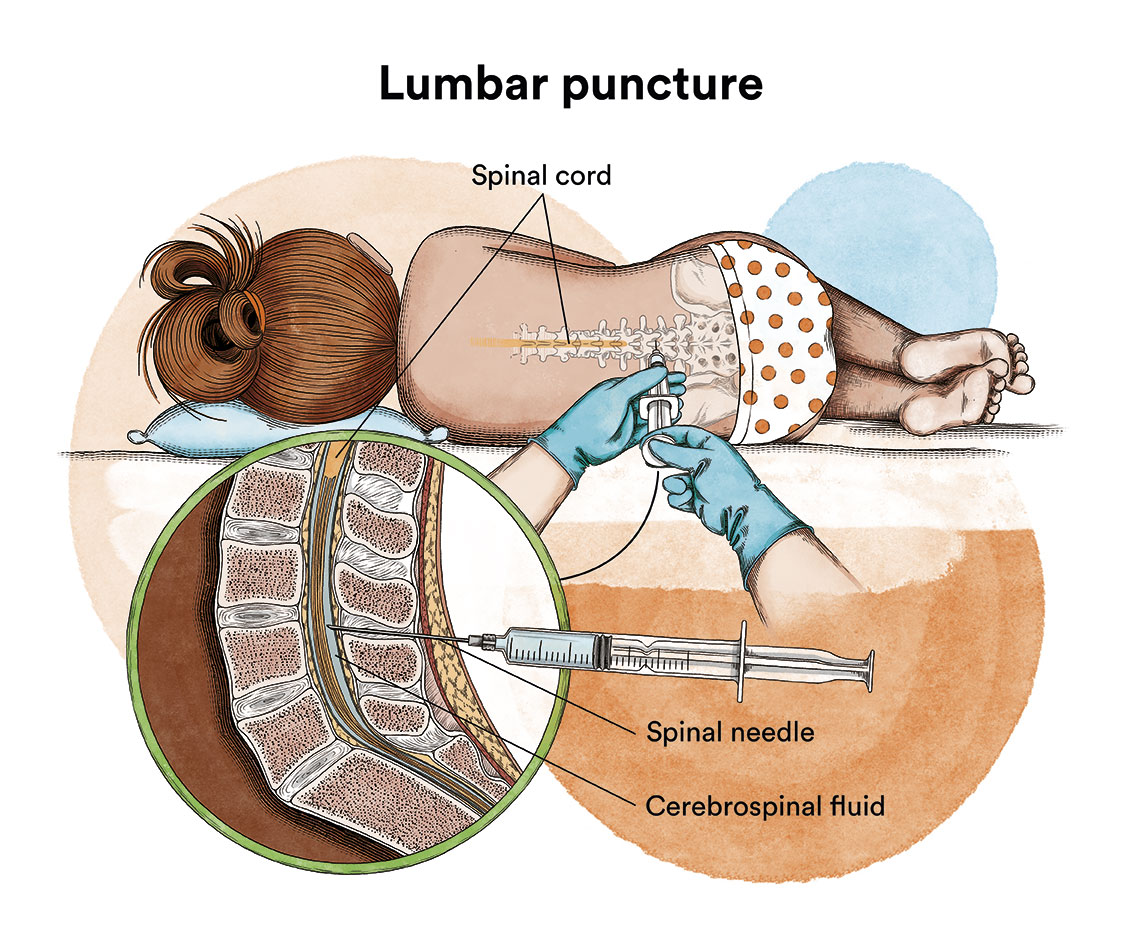

In order to make an accurate diagnosis, several blood and bone marrow extractions (obtained by puncture of the sternum or the hip bone) must be carried out, analysing various aspects such as the leukocyte, red blood cell and platelet counts, and the in-depth study of the lymphoblasts by microscopic observation and the application of other diagnostic techniques such as the study of the phenotype, the study of chromosome alterations and possible altered genes. In addition, X-rays will be taken to assess whether there is enlargement of the lymph nodes inside the chest or abdomen and to assess whether the disease has spread to the central nervous system by means of a lumbar puncture to analyse the cerebrospinal fluid that bathes the central nervous system.

Each treatment for each subtype of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia will be determined on a case-by-case basis taking into account the subtype of the disease, the patient’s age, general condition and, subsequently, the response to initial treatment.

The main goal of any treatment for leukaemia or other haematological malignancies is to achieve complete remission of the disease at a molecular level, i.e. the elimination of as many leukaemic cells as possible. This can now be measured by studying so-called residual disease using specific techniques capable of detecting molecular alterations. To achieve this goal, there are 3 treatment phases in the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukaemias: remission induction, consolidation/intensification and maintenance.

In general, treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia should be started as soon as possible after diagnosis, as it can progress very rapidly.

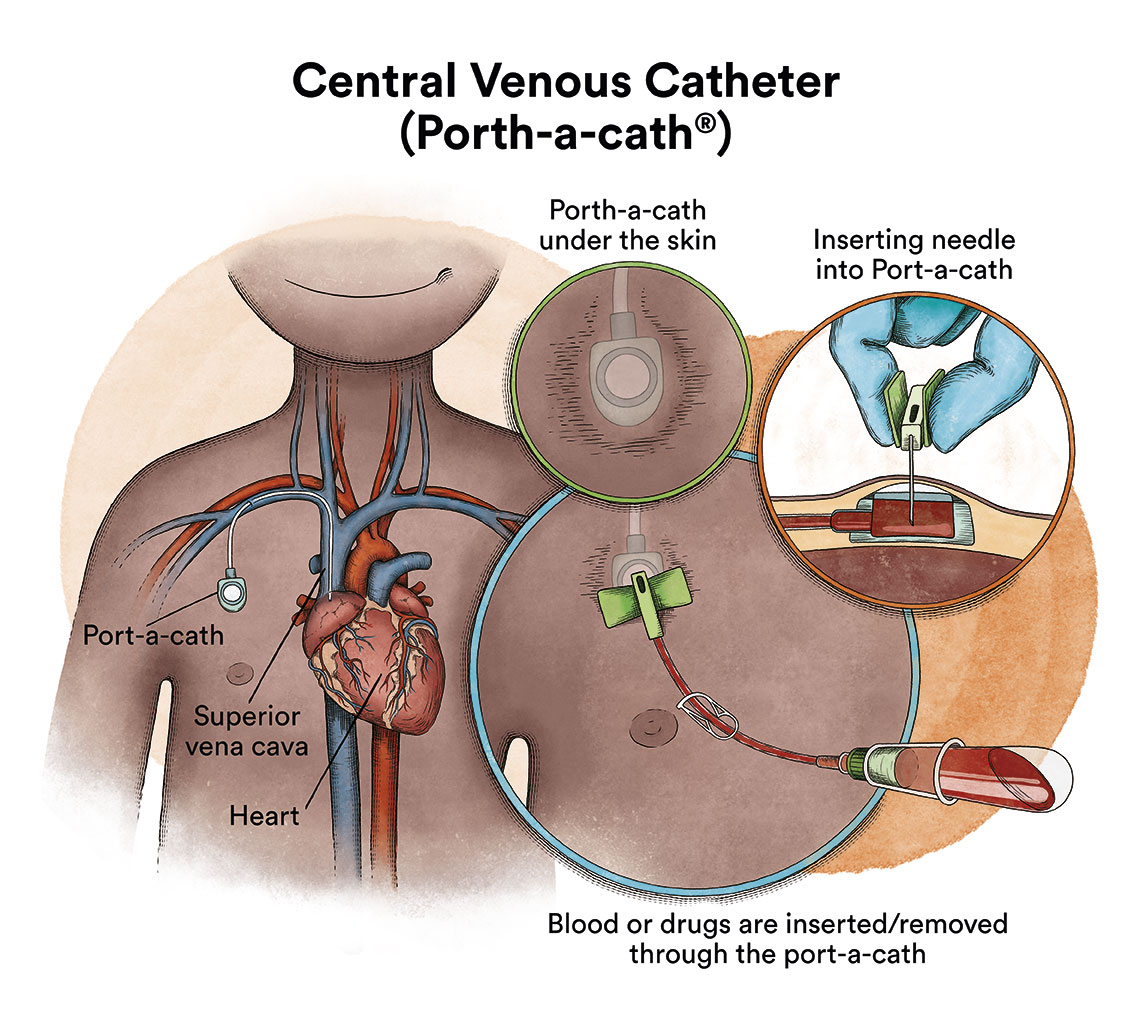

Due to the administration of drugs and/or blood transfusions, acute leukaemia patients are usually fitted with a central venous catheter to facilitate treatment.

1. Remission induction phase

This is always based on intensive chemotherapy, consisting of the administration of various antineoplastic agents intravenously with the aim of making the leukaemic cells disappear from the blood and bone marrow (complete remission), allowing the normal production of other blood cells. A patient is considered to have reached morphological complete remission when the number of blasts in the bone marrow is less than 5%, although what is of prognostic value is the detection of minimal residual disease, for which the response at the immunophenotypic level is studied and in this case the detection of blasts must be equal to or less than 0.01%. This clinical situation is usually reached after the first course of treatment in 80-85% of adults. This phase is brief and intense and usually lasts about a month.

2. Consolidation/intensification treatment phase

This phase aims to destroy residual leukaemic cells (minimal residual disease) that could at any time begin to reproduce and cause a relapse. The number of cycles and their composition may vary according to different therapeutic protocols. This phase is also intense and usually lasts for several months.

3. Maintenance phase

It aims to destroy any remaining leukaemic cells that could reproduce in the long term and lead to relapse. Its duration is two years. During this time, several lumbar punctures must be performed periodically to eliminate possible leukaemic cells in the nervous system in order to administer treatment at this level (intrathecal chemotherapy).

The treatment described so far is usually applied to patients considered standard risk, i.e., those in whom leukaemia has a more favourable prognosis.

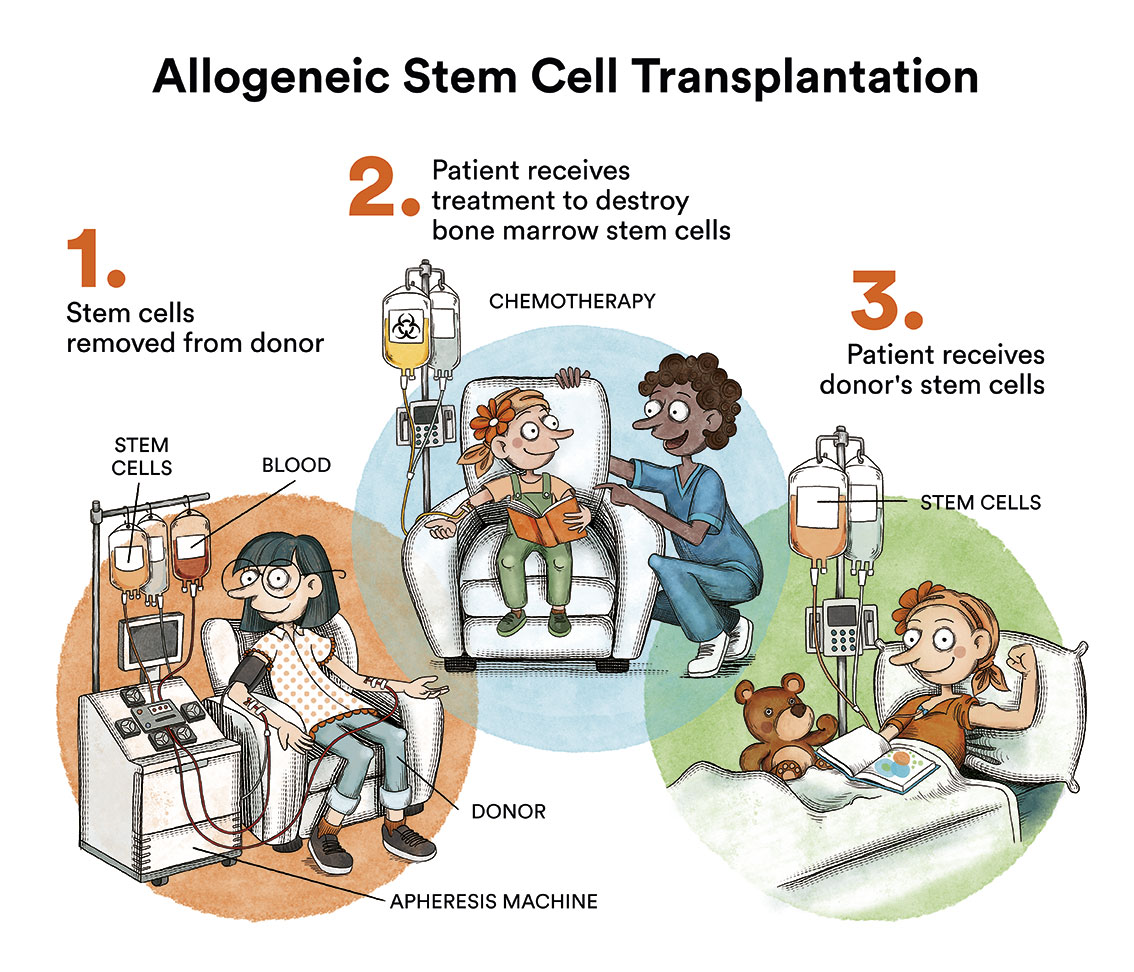

In patients considered high risk (with a high risk of disease relapse, or after a relapse) , a haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (bone marrow, peripheral blood or umbilical cord blood) from a compatible donor (allogeneic transplantation), ideally a histocompatible sibling or, failing that, a globally located unrelated volunteer donor or umbilical cord blood unit, is indicated. Recently, transplants from partially matched relatives (so-called haploidentical transplants) are also used when some of the above-mentioned transplants are not possible.

Autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation is not usually included in standardised treatment protocols for acute lymphoblastic leukaemias due to the high risk of relapse (more than 60%) after transplantation.

External radiotherapy is sometimes used in some subtypes of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia to treat adults with ALL that has spread or is likely to spread to the brain or spinal cord. Total body irradiation is sometimes used to deliver radiation to the whole body in preparation for a stem cell transplant.

Azahar

Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia.

“Shortly before I turned 29, I went to the hospital to donate blood. What was my surprise when I was diagnosed with leukaemia! In addition, it was Philadelphia + acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, a subtype of the disease that requires a bone marrow transplant to cure. Good luck, huh! I was going to donate blood for someone sick! I spent a lot of time, weeks and weeks in isolation and receiving heavy chemotherapy treatments. And, subsequently, I underwent a bone marrow transplant from an anonymous donor located by the Josep Carreras Foundation. Thank you very much to that anonymous donor who gave me a new opportunity to live with my son and my friends.”

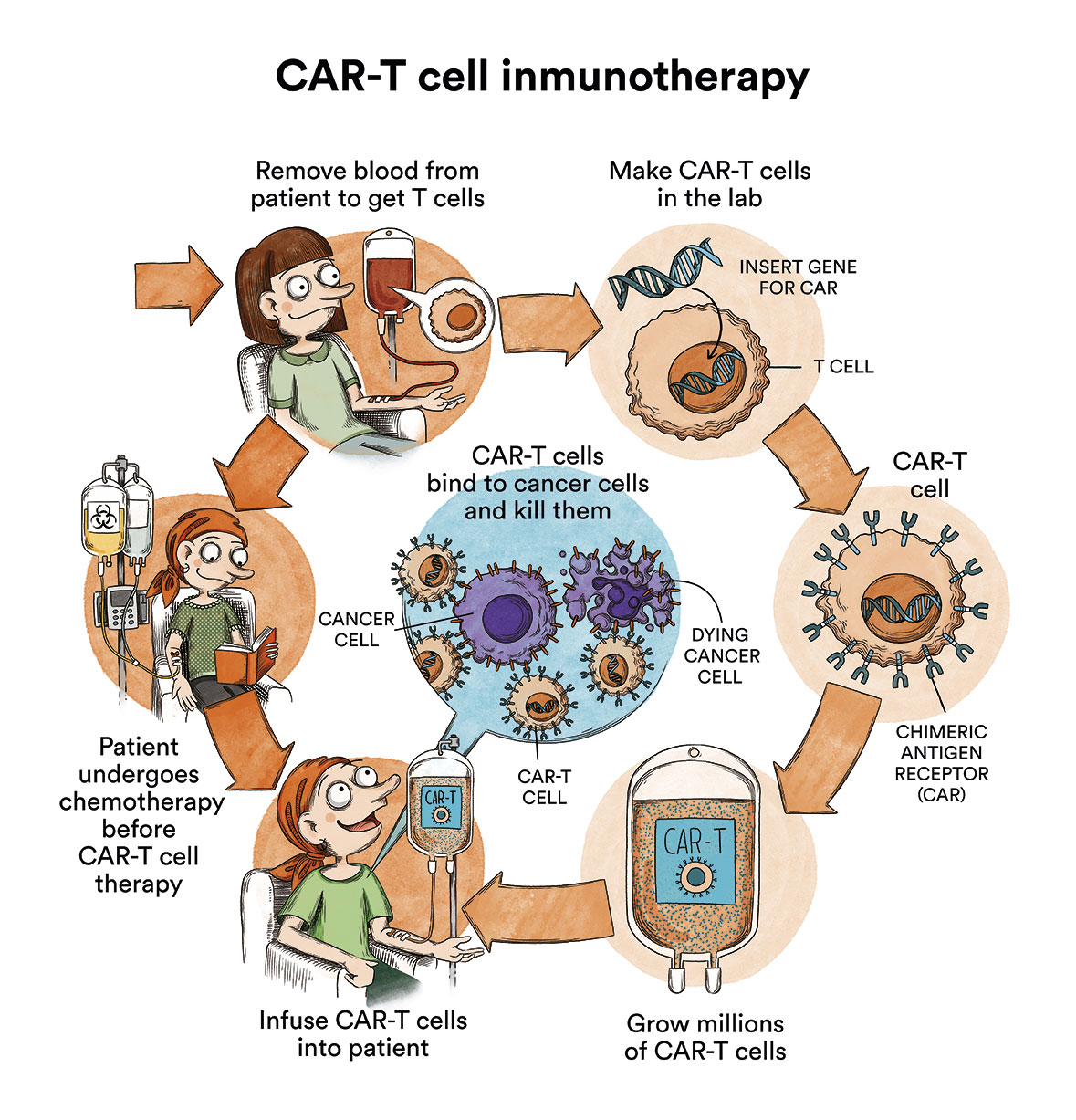

In recent years there has been a revolution in the treatment of cancer and specifically B-acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Among the new treatments available to treat ALL are the treatments known as precision medicine and immunotherapy, especially CAR-T immunotherapy.

Precision medicine is about delivering a personalised treatment targeted against genetic alterations present in the patient’s specific cancer or leukaemia. For example, imatinib has significantly increased the cure rate of children with Philadelphia chromosome ALL (Ph+ ALL).

Immunotherapy treatments are cancer treatments that help the immune system fight cancer. The patient’s own immune system is boosted to help their body fight infections and other diseases. Immunotherapy can be used alone or in combination with chemotherapy or other cancer treatments.

There are various therapies such as:

- Monoclonal antibodies and checkpoint inhibitors

When the immune system detects something harmful, it produces antibodies. Antibodies are proteins that fight infection by binding to antigens. These antigens are molecules that initiate the immune response in the body. Monoclonal antibodies are produced in a laboratory to enhance the body’s natural antibodies or act as antibodies in their own right. Some antibodies block the activity of the cancer cells’ proteins, preventing them from reproducing. Others inhibit or stop immune checkpoints. The body uses the immune checkpoints (check-points) to naturally prevent the immune system from attacking healthy cells. Immune checkpoint inhibitors prevent cancer cells from blocking the immune system. Some of these monoclonal antibodies used in the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukaemias are rituximab, blinatumomab inotuzumab, among others).

- Cellular therapies such as CAR-T immunotherapy

Among other cell therapies, treatment with CAR-T cells has shown promising results in children with B-type ALL. CAR-T lymphocytes are lymphocytes that are extracted from the patient and genetically modified to recognise and destroy the leukaemic cell. See CAR-T Immunotherapy or how to re-engineer one’s own cells to target cancer

Juanxo, 25 years old

Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia.

“I am here, and I remain unstoppable thanks to research. I was diagnosed with leukaemia when I was 19 and underwent a bone marrow transplant from an anonymous donor located by the Foundation. But I had an early relapse. When things were looking worse and doctors were less optimistic, a small thread of hope appeared in the form of a clinical trial: a CAR-T immunotherapy. As they taught me, you must try until the last bullet is exhausted and that is how today I am completely cured.”

- Mature B acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (Burkitt-like). With current treatment regimens, the prognosis for this variety of ALL has improved significantly, with survival rates approaching 70% without the need for transplantation in many cases.

- Philadelphia chromosome + acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Despite progress with the use of the new tyrosine kinase inhibitors (imatinib, dasatinib, nilotinib) alongside intensive chemotherapy, this variety of ALL inevitably requires allogeneic transplantation (from a related or unrelated donor or umbilical cord blood) for its cure (achievable in 50-60% of patients).

Edu, 44 years old

Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia.

“On August 30, 2017, I was born again thanks to a bone marrow transplant from an anonymous donor located by the REDMO program of the Josep Carreras Foundation. I suffered from a very aggressive type of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: Philadelphia+ cromosome. My plan is to be grateful for life every day and enjoy it. We are unstoppable!”.

After completing the treatment, the patient will have regular check-ups performed by their haematologist and other specialists on a case-by-case basis. Monitoring is carried out to assess possible relapse and to follow-up and treat possible long-term complications. These checks are progressively spaced out until they are carried out once a year. Long-term follow-up is recommended at least annually in order to early detection and treatment of any sequelae arising from treatment or leukaemia, should they appear.

The prognosis of patients with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia varies substantially depending on age and the ALL subtype. Advanced age, the degree of initial leukocytosis, the presence of certain genetic/molecular abnormalities, the presence of extramedullary locations (mediastinum, nervous system, testicles), as well as the slowness in obtaining complete remission, among others, constitute unfavourable prognostic parameters.

The prognosis of patients with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia varies substantially depending on age and the ALL subtype. Advanced age, the degree of initial leukocytosis, the presence of certain genetic/molecular abnormalities, the presence of extramedullary locations (mediastinum, nervous system, testicles), as well as the slowness in obtaining complete remission, among others, constitute unfavourable prognostic parameters.

However, the most important prognostic parameter at present is the amount of residual disease patients have after induction and consolidation therapy.

In adult ALL, two prognostic groups are commonly identified: the standard risk ALL (20-25 % of cases with an expected survival rate of 60 % or slightly higher) and the high-risk ALL (with a frequency of 70-75 % and an expected survival rate of 40 %). This classification also makes it possible to modulate the intensity of the patient’s treatment.

These figures are average statistical values which can in no case be applied to individual cases as the evolution of each patient depends absolutely on their condition, age and possible complications. It should be noted that it is a treatable disease, which in many cases provides a chance of cure.

- Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in adults. American Cancer Society.

- Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Treatment. National Cancer Institute

- Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Leukemia & Lymphoma Society

- Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Bloodwise UK

TESTIMONIAL MATERIALS

You can order the booklets in paper format for free delivery in Spain by e-mail: imparables@fcarreras.es

BONE MARROW TRANSPLANT

- Bone Marrow Transplant Guide. Josep Carreras Foundation (content in Spanish)

- What is HLA and how does it work? Josep Carreras Foundation (content in Spanish)

- Graft-versus-Host Disease. Josep Carreras Foundation (content in Spanish)

- History of Bone Marrow Transplantation. Josep Carreras Foundation (content in Spanish)

- How is the search for an anonymous donor conducted? Josep Carreras Foundation (content in Spanish)

FOOD

- How to maintain a healthy diet during treatment? Josep Carreras Foundation (content in Spanish)

- Nutrition guide. Leukemia & Lymphoma Society

OTHER

- Ideas on what to take with me to the isolation chamber. Josep Carreras Leukaemia Foundation (content in Spanish)

- Travel tips for people with cancer. Josep Carreras Leukaemia Foundation (content in Spanish)

- Physiotherapy manual for haematological and transplant patients. Josep Carreras Leukaemia Foundation (content in Spanish)

- Prevention and treatment of oral mucositis. Josep Carreras Leukaemia Foundation (content in Spanish)

- Oral hygiene in oncohaematological patients. Josep Carreras Leukaemia Foundation (content in Spanish)

- Fertility manual: Suffering from blood cancer and becoming a parent. Josep Carreras Leukaemia Foundation (content in Spanish)

- Skin care in the oncohaematological patient. Josep Carreras Leukaemia Foundation (content in Spanish)

- Aesthetic Oncology Manual. Josep Carreras Leukaemia Foundation (content in Spanish)

- Leukaemia and sexuality. Josep Carreras Leukaemia Foundation (content in Spanish)

- 7 ways to wear a scarf. Josep Carreras Leukaemia Foundation (content in Spanish)

In Spain there is a large network of associations for haematological cancer patients that, in many cases, can inform you, advise you and even carry out certain procedures. These are the contacts of some of them by Autonomous Communities:

All these organisations are external to the Josep Carreras Foundation.

STATE

- CEMMP (Comunidad Española de Pacientes de Mieloma Múltiple)

- AEAL (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA DE AFECTADOS POR LINFOMA, MIELOMA y LEUCEMIA)

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present is the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact with the nearest branch or call 900 100 036 (24h).

- AELCLES (Agrupación Española contra la Leucemia y Enfermedades de la Sangre)

- Josep Carreras Leukaemia Foundation

- FUNDACIÓN SANDRA IBARRA

- GEPAC (GRUPO ESPAÑOL DE PACIENTES CON CÁNCER)

- MPN España (Asociación de Afectados Por Neoplasias Mieloproliferativas Crónicas)

ANDALUCÍA

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present is the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

- ALUSVI (ASOCIACIÓN LUCHA Y SONRÍE POR LA VIDA). Sevilla

- APOLEU (ASOCIACIÓN DE APOYO A PACIENTES Y FAMILIARES DE LEUCEMIA). Cádiz

ARAGÓN

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present is the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

- ASPHER (ASOCIACIÓN DE PACIENTES DE ENFERMEDADES HEMATOLÓGICAS RARAS DE ARAGÓN)

- DONA MÉDULA ARAGÓN

ASTURIAS

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present is the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

- ASTHEHA (ASOCIACIÓN DE TRASPLANTADOS HEMATOPOYÉTICOS Y ENFERMOS HEMATOLÓGICOS DE ASTURIAS)

CANTABRIA

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present is the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

CASTILLA LA MANCHA

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present is the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

CASTILLA LEÓN

- ABACES (ASOCIACIÓN BERCIANA DE AYUDA CONTRA LAS ENFERMEDADES DE LA SANGRE)

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present is the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

- ALCLES (ASOCIACIÓN LEONESA CON LAS ENFERMEDADES DE LA SANGRE). León.

- ASCOL (ASOCIACIÓN CONTRA LA LEUCEMIA Y ENFERMEDADES DE LA SANGRE). Salamanca.

CATALUÑA

- ASSOCIACIÓ FÈNIX. Solsona

- FECEC (FEDERACIÓ CATALANA D’ENTITATS CONTRA EL CÁNCER

- FUNDACIÓ KÁLIDA. Barcelona

- FUNDACIÓ ROSES CONTRA EL CÀNCER. Roses

- LLIGA CONTRA EL CÀNCER COMARQUES DE TARRAGONA I TERRES DE L’EBRE. Tarragona

- MielomaCAT

- ONCOLLIGA BARCELONA. Barcelona

- ONCOLLIGA GIRONA. Girona

- ONCOLLIGA COMARQUES DE LLEIDA. Lleida

- ONCOVALLÈS. Vallès Oriental

- OSONA CONTRA EL CÀNCER. Osona

- SUPORT I COMPANYIA. Barcelona

- VILASSAR DE DALT CONTRA EL CÀNCER. Vilassar de Dalt

VALENCIAN COMMUNITY

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present is the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

- ASLEUVAL (ASOCIACIÓN DE PACIENTES DE LEUCEMIA, LINFOMA, MIELOMA Y OTRAS ENFERMEDADES DE LA SANGRE DE VALENCIA)

EXTREMADURA

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present is the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

- AFAL (AYUDA A FAMILIAS AFECTADAS DE LEUCEMIAS, LINFOMAS; MIELOMAS Y APLASIAS)

- AOEX (ASOCIACIÓN ONCOLÓGICA EXTREMEÑA)

GALICIA

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present is the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

- ASOTRAME (ASOCIACIÓN GALLEGA DE AFECTADOS POR TRASPLANTES MEDULARES)

BALEARIC ISLANDS

- ADAA (ASSOCIACIÓ D’AJUDA A L’ACOMPANYAMENT DEL MALALT DE LES ILLES BALEARS)

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present is the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

CANARY ISLANDS

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present is the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

- AFOL (ASOCIACIÓN DE FAMILIAS ONCOHEMATOLÓGICAS DE LANZAROTE)

- FUNDACIÓN ALEJANDRO DA SILVA

LA RIOJA

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present is the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

MADRID

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present is the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

- AEAL (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA DE LEUCEMIA Y LINFOMA)

- CRIS CONTRA EL CÁNCER

- FUNDACIÓN LEUCEMIA Y LINFOMA

MURCIA

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present is the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

NAVARRA

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present is the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

BASQUE COUNTRY

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present is the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

- PAUSOZ-PAUSO. Bilbao

AUTONOMOUS CITIES OF CEUTA AND MELILLA

- AECC CEUTA (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER)

- AECC MELILLA (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER)

We also invite you to follow us through our main social media (Facebook, Twitter and Instagram) where we often share testimonies of overcoming this disease.

If you live in Spain, you can also contact us by sending an e-mail to imparables@fcarreras.es so that we can help you get in touch with other people who have overcome this disease.

* In accordance with Law 34/2002 on Information Society Services and Electronic Commerce (LSSICE), the Josep Carreras Leukemia Foundation informs that all medical information available on www.fcarreras.org has been reviewed and accredited by Dr. Enric Carreras Pons, Member No. 9438, Barcelona, Doctor in Medicine and Surgery, Specialist in Internal Medicine, Specialist in Hematology and Hemotherapy and Senior Consultant of the Foundation; and by Dr. Rocío Parody Porras, Member No. 35205, Barcelona, Doctor in Medicine and Surgery, Specialist in Hematology and Hemotherapy and attached to the Medical Directorate of the Registry of Bone Marrow Donors (REDMO) of the Foundation).

Information reviewed in November 2023.

Become a member of the cure for leukaemia!