Myelodysplastic syndromes

Myelodysplastic syndromes are a heterogeneous group of malignant blood diseases. They account for more than 2,000 diagnoses per year in our country.

The information provided on www.fcarreras.org is intended to support, not replace, the relationship that exists between patients/visitors to this website and their physician.

Anna

Myelodysplastic syndrome.

“On October 5, 2020, I was diagnosed with high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome. If I didn’t have a bone marrow transplant, I could live a few months. I had never had any illness and I couldn’t believe it. I underwent several sessions of chemotherapy and, later, my brother’s bone marrow transplant. Little by little I am recovering but always with a big smile”.

Information provided by Dra. Blanca Xicoy. Clinical Haematology Unit; Institut Català d’Oncologia- Badalona; Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol. Josep Carreras Leukaemia Research Institute. Barcelona Medical Association (Co. 30566).

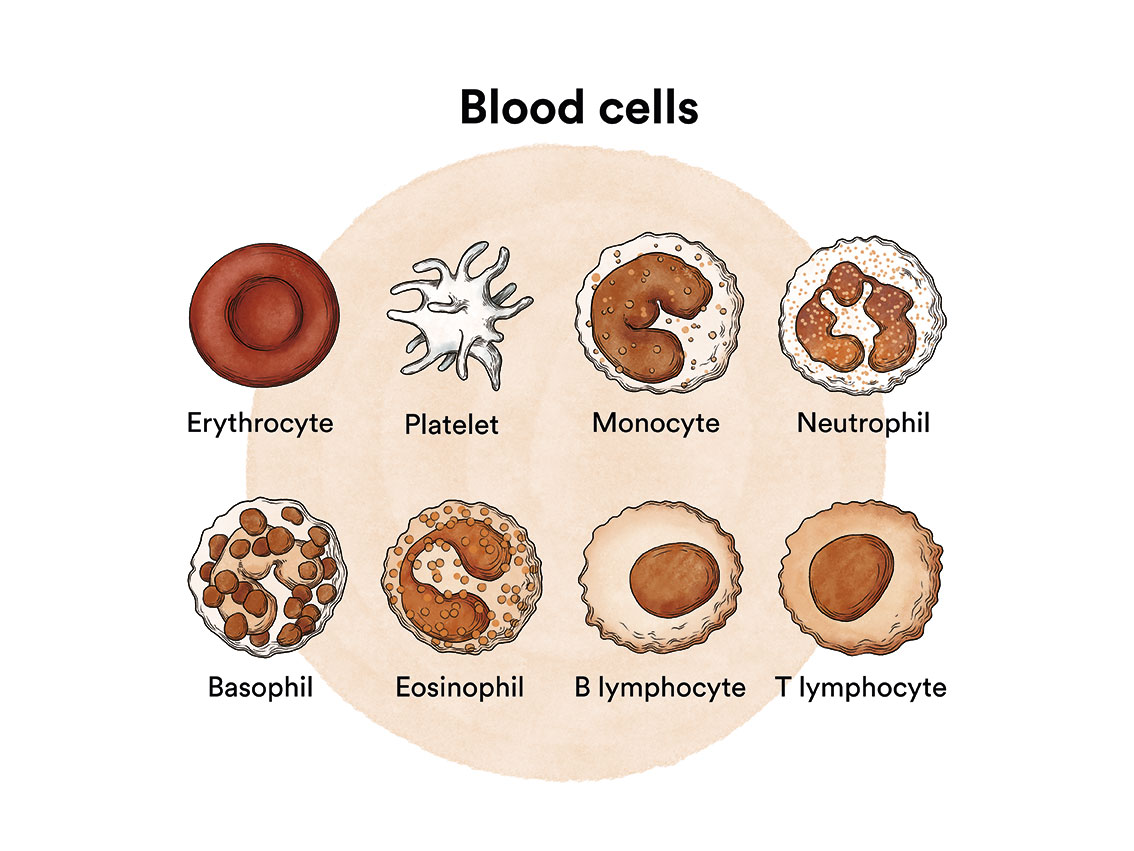

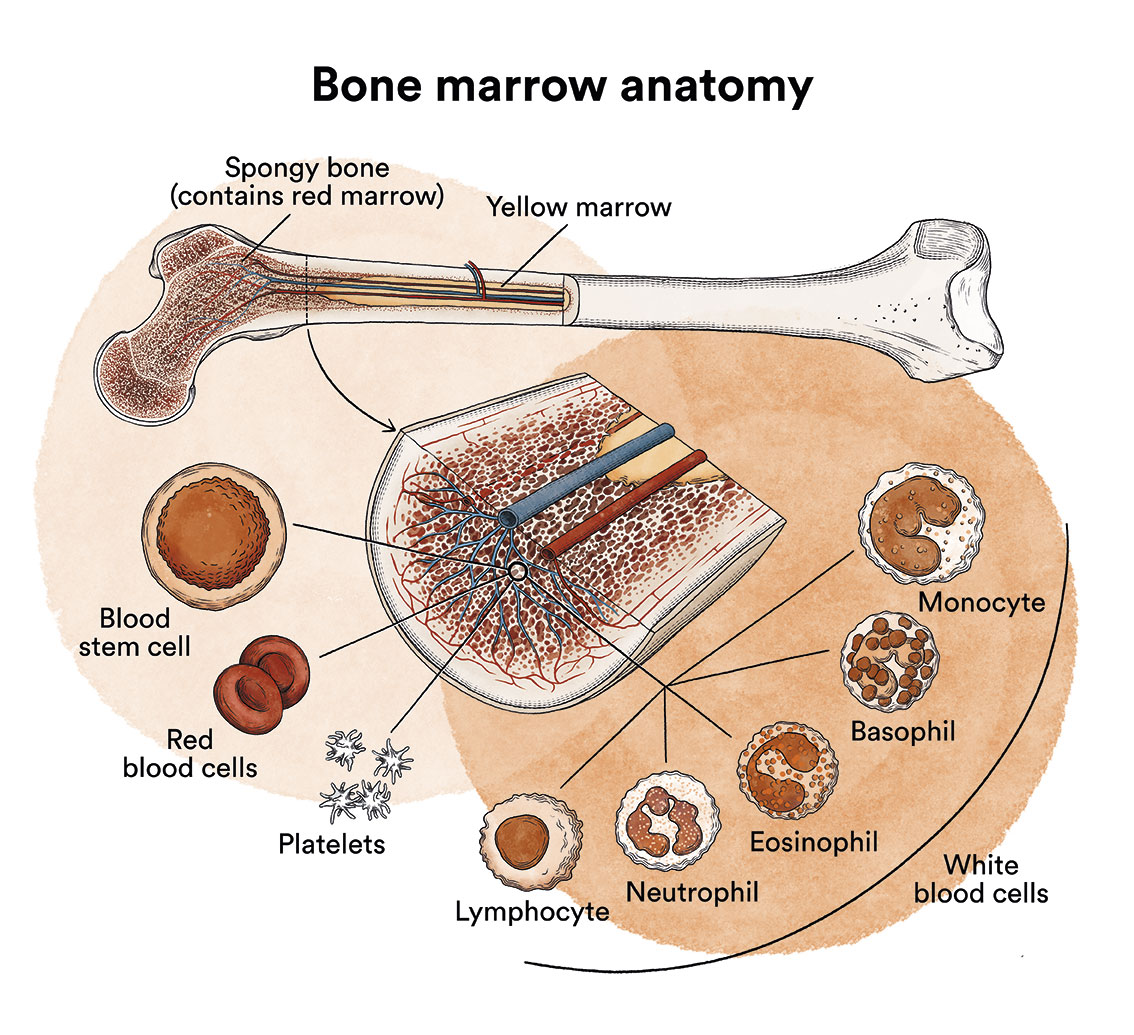

How does bone marrow work and what are the types of blood cells?

Myelodysplastic syndromes are a type of blood cell and bone marrow cancer.

See section Leukaemia, bone marrow and blood cells.

What are myelodysplastic syndromes?

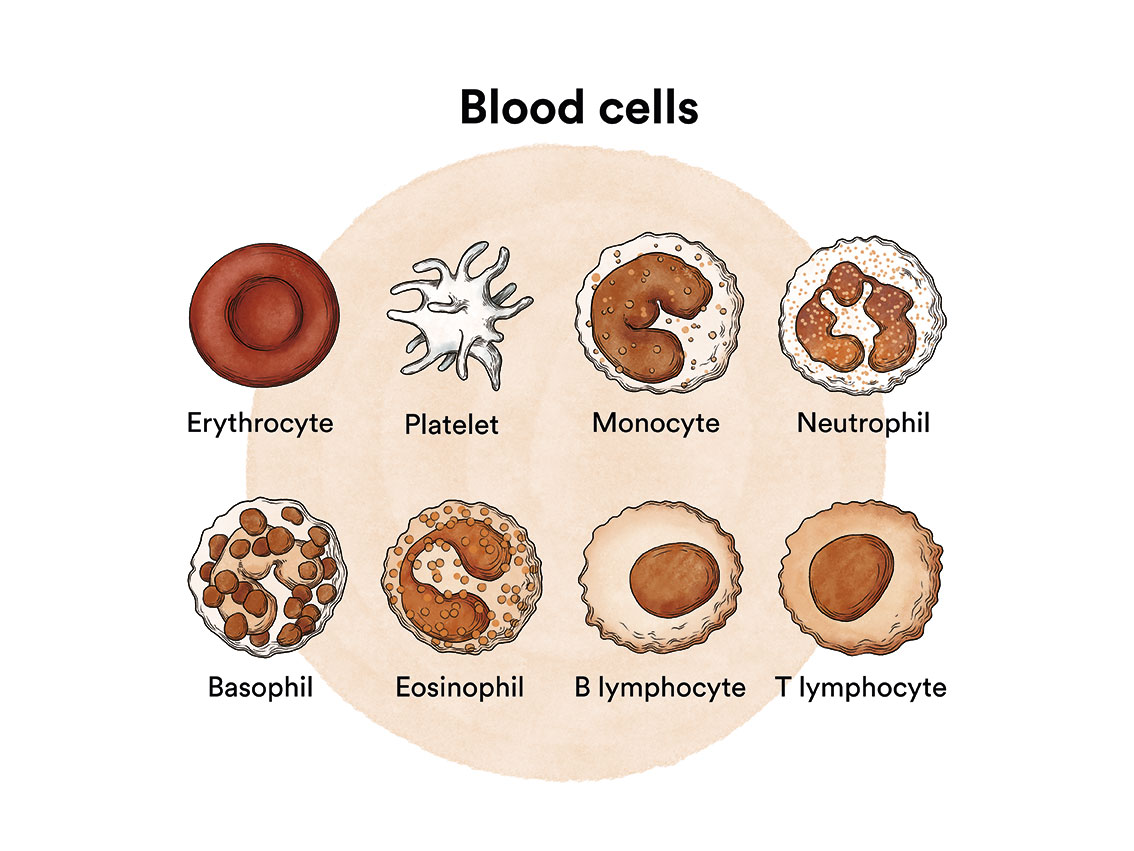

Myelodysplastic syndromes are a type of disease of the bone marrow, the organ responsible for making blood cells (red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets). Under normal conditions, these cells reproduce and mature in the bone marrow until they emerge and circulate in the blood. In myelodysplastic syndromes, the bone marrow produces these cells abnormally, both in number and in maturation or function, and these abnormalities are detected in the blood when we run a blood test (haemogram) and look at the blood under a microscope.

In myelodysplastic syndromes there is usually a decreased number of some of the blood cells with some morphological (dysplastic) alterations. In a myelodysplastic syndrome patient, the blood stem cells (immature cells) in the bone marrow do not develop into mature red blood cells, white blood cells or platelets. These immature blood cells, called blasts, do not function as they should and die in the bone marrow or shortly after entering the blood. This leaves less room for healthy white blood cells, red blood cells and platelets to form in the bone marrow. When there are fewer healthy blood cells, infections, anaemia or easy bleeding may occur.

In addition, in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes, there are DNA alterations affecting chromosomes, genes (mutations) or methylation (DNA modifications that can disable the function of a gene) and also other DNA-related structures.

What are the different types of myelodysplastic syndromes?

MDS form a heterogeneous group of diseases with very different prognoses and treatments. The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies MDS according to the percentage of precursor cells in the bone marrow that show dysplasia (appear abnormal under the microscope), what percentage of primitive red blood cells are ring sideroblasts (cells containing rings of iron deposits around the nuclei), what percentage of blasts are in the bone marrow or blood (very immature blood cells) and certain chromosomal alterations. This classification differentiates between the following subtypes of MDS:

1. Myelodysplastic syndrome with single lineage dysplasia (MDS-SLD)

Dysplasia is seen in at least 10% of 1 type of red blood cell precursor cells, white blood cells and/or megakaryocytes (the cells that produce platelets) in the bone marrow.

The person has low counts of one or 2 types of blood cells, but a normal number of other type(s).

There is a normal number (less than 5%) of very primitive cells called blasts in the bone marrow. In addition, there are very few (or no) blasts in the blood.

It is rare for this type of myelodysplastic syndrome to progress to acute myeloid leukaemia (AML). Patients with this type of myelodysplastic syndrome can sometimes live a long time, even without treatment. In the previous classification, WHO-2008 referred to refractory anaemia (RA), refractory neutropaenia (RN) and refractory thrombocytopaenia (RT), depending on the cell type affected.

2. Myelodysplastic syndrome with multilineage dysplasia (MDS-MLD)

Dysplasia is seen in at least 10% of 2 or 3 types of red blood cell precursor cells, white blood cells and/or megakaryocytes (the cells that produce platelets) in the bone marrow.

The person has low counts of at least one type of blood cell.

There is a normal number (less than 5%) of very primitive cells called blasts in the bone marrow. In addition, there are very few (or no) blasts in the blood.

This is the type of MDS that in the past, according to the WHO-2008 classification, was called refractory cytopaenia with multilineage dysplasia (RCMD).

If red blood cells are affected, they may have extra iron. Treatment-resistant cytopaenia can progress to acute myeloid leukaemia (AML).

3. Myelodysplastic syndrome with ring sideroblasts (MDS-RS)

In this type of myelodysplastic syndrome, many of the precursor cells of red blood cells are ring sideroblasts (cells containing rings of iron deposits around the nuclei). For this diagnosis, at least 15% of the primitive red blood cells (erythroblasts) have to be ring sideroblasts (or at least 5% if the cells also have a mutation in the SF3B1 gene).

This condition is subdivided into two types, based on how many of the cell types in the bone marrow are affected by the dysplasia (abnormality of the cells):

- Myelodysplastic syndrome with ring sideroblasts with single lineage dysplasia (MDS-RS-SLD): dysplasia in a single cell type.

- Myelodysplastic syndrome with ring sideroblasts with multilineage dysplasia (MDS-RS-MLD): dysplasia in more than one cell type.

It is a rare subtype of myelodysplastic syndrome. It rarely transforms to acute myeloid leukaemia and, in general, the prognosis is better than in other types of MDS. Previously, the WHO-2008 classification referred to this subtype as refractory anaemia with ring sideroblasts (RARS).

Andrew

Myelodysplastic syndrome.

“When I was 24 years old, I was diagnosed with high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome. Everything stopped. I had to leave my life and take another path. The path of fatigue, nausea, treatments, the hospital, the bone marrow transplant, … A loop that seemed impossible to get out of. But my family, my partner, my friends, and the exceptional team at the hospital were there to give me the push I needed. Little by little the days began to be less grey and that’s when I took the plunge to start a new life. Since that day of the transplant, I can’t do anything but smile and enjoy.”

4. Myelodysplastic syndrome with excess blasts (MDS-EB)

In this subtype there are more blasts (immature blood cells) than normal in the bone marrow and/or blood. The person also has low counts of at least one type of blood cell. Severe bone marrow dysplasia may or may not be present.

This condition is subdivided into two types, based on what percentage of the bone marrow is blasts:

- Myelodysplastic syndrome with excess blasts (MDS-EB1): blasts constitute 5% to 9% of the cells in the bone marrow, or 5% to 19% of the cells in the blood.

- Myelodysplastic syndrome with excess blasts (MDS-EB2): blasts constitute 10-19% of the cells in the bone marrow, or 2-4% of the cells in the blood.

This subtype accounts for about 25% of all diagnoses of myelodysplastic syndromes. It is one of the types most likely to develop into acute myeloid leukaemia, especially in the MDS-EB2 subtype. Previously, the WHO-2008 classification referred to this subtype as refractory anaemia with excess blasts (RAEB).

5. Myelodysplastic syndrome with isolated del of chromosome 5 (5q- syndrome)

In this type of myelodysplastic syndrome, the chromosomes are missing part of chromosome 5. There may also be another chromosomal abnormality, as long as it is not the loss of all or part of chromosome 7. The number of blasts is normal.

The person also has low counts of one or 2 types of blood cells (usually red blood cells), and there is dysplasia in at least one type of cell in the bone marrow.

This type of myelodysplastic syndrome is rare and occurs more often in older women. For reasons that are unclear, patients with this type of myelodysplastic syndrome usually have a favourable prognosis. They often live for a long time and rarely progress to acute myeloid leukaemia.

6. Unclassifiable myelodysplastic syndrome (MSD-U)

This category includes rare myelodysplastic syndromes. Some may have cytogenetic alterations typical of other MDS without dysplasia or relevant blood cell alterations.

There are two other types of myelodysplastic syndromes to consider that are not included in the World Health Organization classification. These are:

- Secondary myelodysplastic syndromes: those that are triggered in people who have previously received chemotherapy or radiotherapy treatment for another type of cancer. People with this type of MDS tend to have a worse prognosis than those with regular MDS.

- Hypoplastic myelodysplastic syndrome: In this type, few blood stem cells are seen in the bone marrow. In this case, the sick body’s defences attack the stem cells in the bone marrow, causing many of them to be eliminated. As this hypoplastic type of MDS has a special mechanism, its treatment is also special. Drugs that reduce the strength of our defences, so-called “immunosuppressants”, are often used.

What are the causes of myelodysplastic syndromes?

It is not known why myelodysplastic syndromes occur, but in most cases, these are acquired diseases related to ageing or due to environmental exposure, occupational or otherwise, to toxic substances or treatments such as radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy, among others.

Myelodysplastic syndromes, like other cancers, is not contagious. See section Leukaemia, bone marrow and blood cells.

What are the symptoms of myelodysplastic syndromes?

In the early stages of myelodysplastic syndromes, patients often do not feel any discomfort. In these cases, the myelodysplastic syndrome diagnosis is usually discovered after results indicating low blood cell counts in a control blood test or for other medical procedures.

In cases in which the patient feels unwell and visits their doctor, the symptoms and severity will depend on the type of cells affected and on how low the blood cell counts are.

If there is anaemia due to a decrease in red blood cells , tiredness and weakness are common (when it is severe, the patient may also experience dizziness, palpitations, sweating…). In more severe cases there may be symptoms resulting from decreased white blood cells and/or platelets leading to infections and/or haemorrhages, respectively.

When proliferative disorders predominate, there is a risk of thrombosis as the increase in red blood cells and/or platelets can clog blood vessels, especially if the person smokes, has cholesterol or high blood pressure.

In addition, as the bone marrow works at a faster rate than normal, the liver and spleen may increase in size so that they also contribute to this proliferation; this increase in size can lead to abdominal discomfort (bloating, pain, constipation…).

There may also be symptoms such as tiredness, lack of appetite, weight loss, itching (these are known as constitutional symptoms).

How are myelodysplastic syndromes diagnosed?

In addition to basic blood and bone marrow studies (morphology, blood count, immunophenotyping), cytogenetic studies (to detect specific chromosomal abnormalities) and molecular studies (to detect specific genetic alterations) are essential for typing and classifying the disease. Certain genetic and molecular alterations correlate with treatment sensitivity and prognosis.

In short, to diagnose MDS, the following must be studied:

1) Analysis with microscopic study of the blood cells, where we will see alterations in the number and shape of the cells;

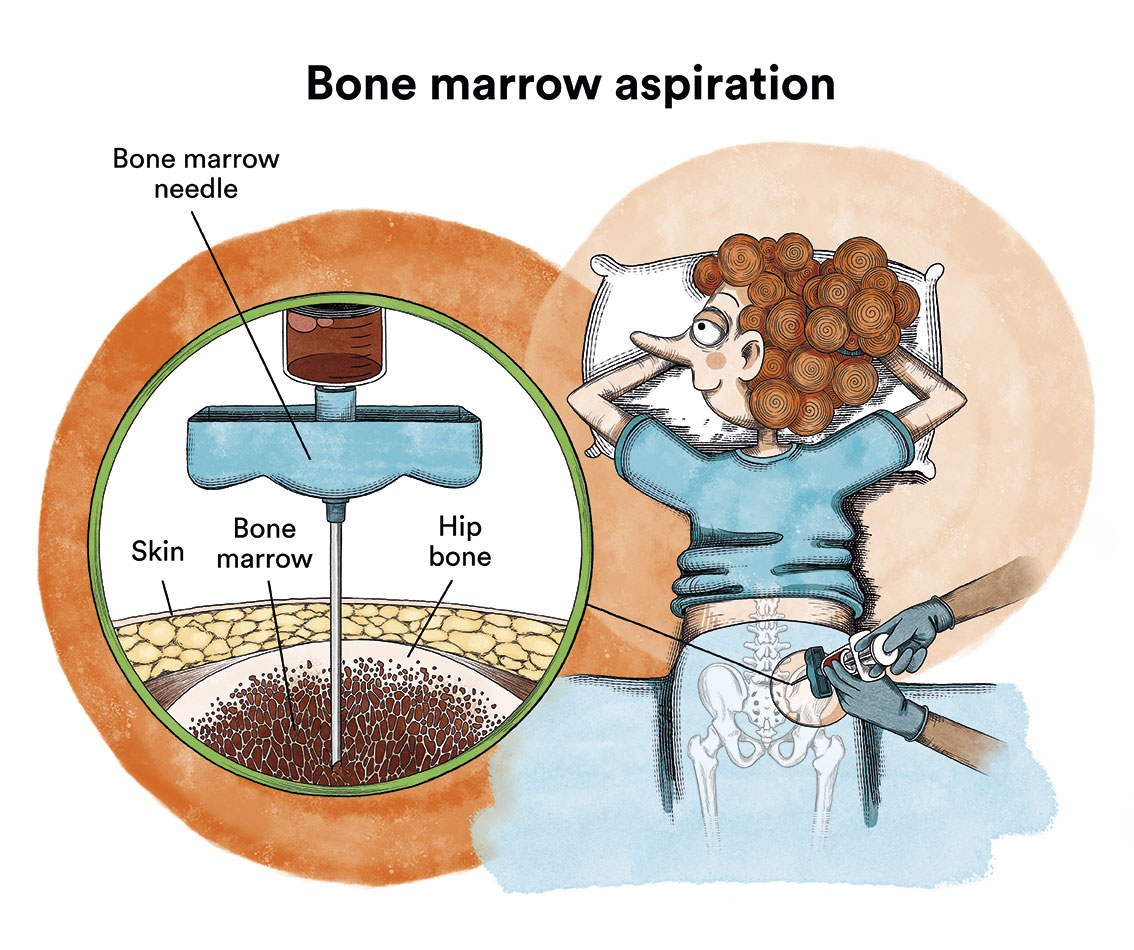

2) Bone marrow aspirate: we will observe that the predecessor cells of the blood cells are in much greater quantity than normal and, in them, there are alterations in shape and size; we will observe a variable percentage of abnormal immature cells (blasts) with possible alterations in their chromosomes and genes; and, finally, we will observe ring sideroblasts or not; cytogenetic and molecular studies are also carried out with the aspirate, which are key to determining the risk and prognosis of the disease.

3) Bone marrow biopsy: this is performed to confirm the diagnosis and, in it, we will see a considerable increase in the number of cells in the bone marrow and we may find a mild-moderate degree of fibrosis (a kind of “net or cloth” that hinders the normal functioning of the bone marrow).

What is the treatment for myelodysplastic syndromes?

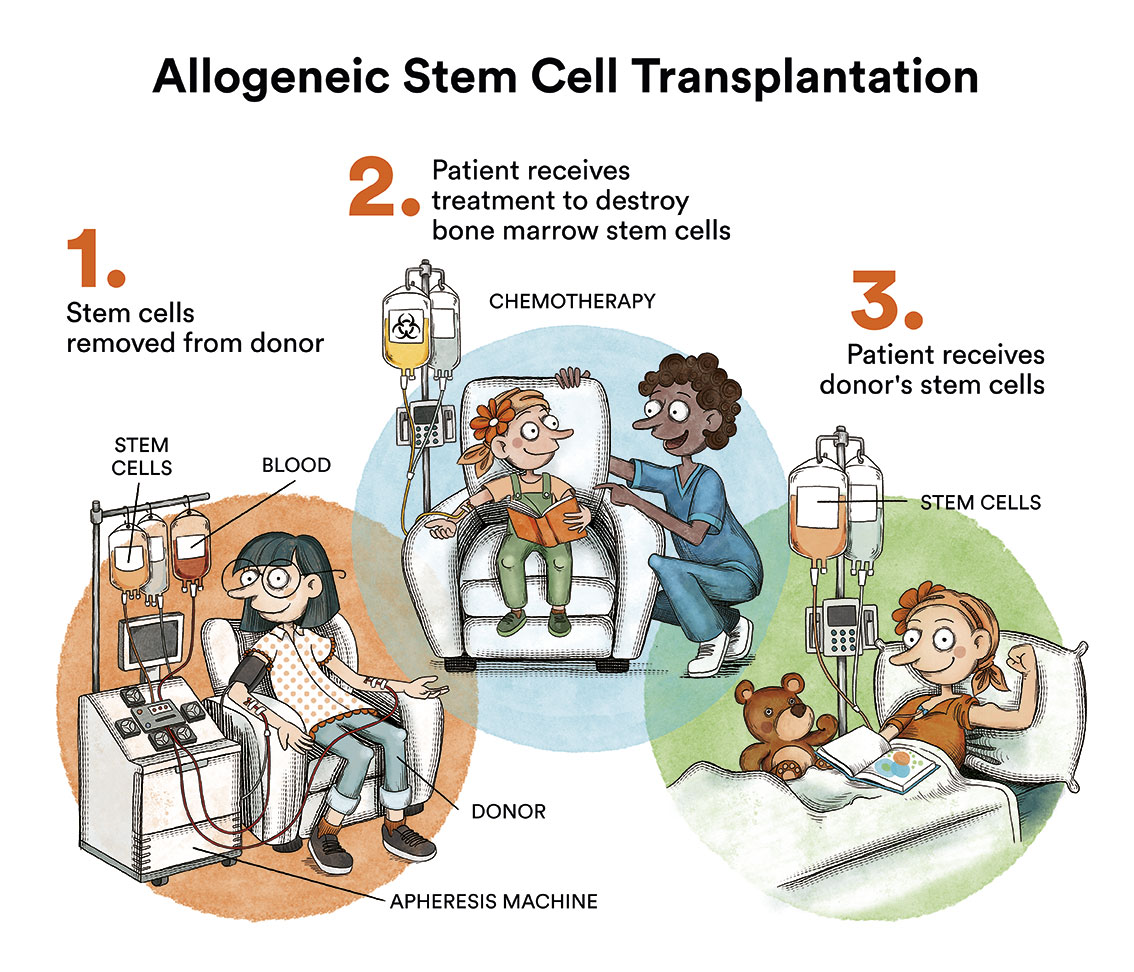

As discussed above, there are many types of myelodysplastic syndromes with very different characteristics and treatments. The only curative treatment would be an allogeneic bone marrow transplant (donor), but due to its risks, it is only reserved for MDS at high risk of transforming into acute myeloid leukaemia and in young patients.

Juan

Myelodysplastic syndrome.

“In 2019, when I was only 29 years old, I was diagnosed with high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome after an analysis that I requested because I felt very tired, with headaches, dizziness, … The truth is that it was a shock. I always have been a healthy person without bad habits. My life changed in a second. I underwent several sessions of chemotherapy and a bone marrow transplant from an anonymous donor located by the Josep Carreras Foundation. These moments are very hard, but I always try to be with a smile and be grateful for every day of life.”

An internationally agreed prognostic system is used to establish the level of risk for each of the myelodysplastic syndromes and is constantly being revised. In other words, it is a system that aims to elucidate more precisely whether the disease will be more or less aggressive. This index is called the IPSS-R and is based on data from thousands of patients internationally. This index is based on:

- the number of blasts in the bone marrow

- type of blood cells that are altered (red blood cells, platelets and neutrophils)

- whether the bone marrow cells have altered chromosomes.

A detailed version of this system can be seen in the following tables:

International Prognostic System Revised (IPSS-R)

.

| Variable | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 1.5 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Cytogenic | Very good | – | Good | – | Intermediate | Poor | Very Poor |

| Blasts in bone marrow | Less than 2% | – | 3 or 4% | – | Between 5 and 10% | More than 10% | – |

| Haemoglobin level (in grams per decilitre) | More than 10 | – | Less than 10 and more than 8 | Less than 8 | – | – | – |

| Number of platelets per microlitre of blood | More than 100,000 | Between 50,000 and 100,000 | Less than 50,000 | – | – | – | – |

| Number of neutrophils per microlitre of blood | More than 800 | Less than 800</ | – | – | – | – | – |

The IPSS-R prognostic system divides chromosomal disorders into five groups according to their risk:

- Very good: males who lose the Y chromosome or cases where a fragment of chromosome 11 is lost.

- Good: cases with normal cytogenetics or with a single alteration consisting of the loss of a segment of chromosome 5, 12 or 20. Also cases where there are two alterations if one of them is of chromosome 5.

- Intermediate: if there is a single alteration consisting of the loss of a segment of chromosome 7, or the appearance of a third chromosome 8, or a third chromosome 19. Also the appearance of an altered chromosome 17.

- Poor: complete loss of chromosome 7, alterations in chromosome 3, cases with three alterations together or two if one of them is a partial or complete loss of chromosome 7.

- Very poor: the so-called complex cases, in which there are more than three alterations at the same time.

Depending on the total score of all these factors, the risk according to the IPSS-R will be:

Prognostic groups of the International Prognostic System Revised (IPSS-R)

| Risk groups | Total points | Median survival in years (untreated) | Median number of years until 1 in 4 patients in this group develop acute leukaemia (untreated) |

| Very low risk | Less than 1.5 | 8.8 | Not reached |

| Low risk | More than 1.5 and less than 3 | 5.5 | 10.8 |

| Intermediate risk | More than 3 and less than 4.5 | 3 | 3.2 |

| High risk | More than 4.5 and less than 6 | 1.6 | 1.4 |

| Very high risk | More than 6 | 0.8 | 0.7 |

For myelodysplastic syndromes we currently have few effective treatments and no defined treatment regimen. However, there are specific treatment response criteria for these diseases. In general, consideration is given to which features (dysplastic or proliferative) predominate in each patient. Therefore, different treatment options are considered:

- If the drop in blood cell levels is mild and the type of MDS is low risk, it is sufficient to try to control the patient’s symptoms. The most reasonable course of action may be to “watch and wait”, and not to opt for treatment or transfusions. In these cases, blood levels are monitored by regular blood tests and, if there is any change, further testing would be done to assess it. This type of therapeutic approach generates a lot of uncertainty for patients and there is often a feeling of “passivity” on the part of the medical team. But it has been proven that, for the time being, this is the best option for some types of MDS. The only curative option for MDS is an allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. However, this therapy has a significant life-threatening risk and sequelae and should therefore be reserved for high-risk patients.

- In young patients (<70 years), without other serious pathologies, with moderate or high risk of MDS transforming into acute leukaemia, the treatment of choice should be to cure the disease by an allogeneic bone marrow transplantation (donor), which is the only curative treatment, although there may be serious complications from infections and/or rejection of the transplanted bone marrow. On these occasions, the use of various oral and/or intravenous chemotherapies is considered.

- In patients at moderate or high risk where a bone marrow transplant cannot be performed, either due to age or other serious non-compatible pathologies, the most sensible approach is to perform blood transfusions when needed and to try to delay disease progression with drugs. In these cases neither cure nor modification of the natural course of the disease is possible.

Blood transfusions (supportive therapy)

Many patients with myelodysplastic syndromes are highly dependent on blood transfusions due to the depletion of certain blood cells. These transfusions are usually performed in the day hospital on an outpatient basis. Red blood cell transfusions are common in some patients. However, sometimes it may also be necessary to receive a transfusion of platelets or white blood cell stimulating factors (G-CSF).

Side effects of blood transfusion therapy are rare, but transfusion reactions, infections, development of antibodies to red blood cells or platelets, and iron overload in different organs of the body may be observed.

New treatments: disease-modifying therapies

When a cure for a myelodysplastic syndrome is not possible because the patient cannot undergo a bone marrow transplant, there are drugs that can modify the course of the disease in order to improve bone marrow function. Some of them are:

- Azacitidina (Vidaza®): which is commonly used to prevent dependence on blood transfusions, to prevent bleeding and/or infections. Azacitidine belongs to a class of medicines called demethylating agents. It works by helping the bone marrow to produce normal red blood cells and destroying abnormal cells in the bone marrow. Apart from bone marrow transplantation, azacitidine is the first treatment that has proven to delay progression to acute leukaemia and prolong life in patients with high-risk MDS. Not least, it has also been shown to improve the quality of life of treated patients.

- Lenalidomide (Revlimid®): is a drug used in some low-risk myelodysplastic syndromes if they have anaemia and a lesion of chromosome 5 (5q-). Lenalidomide belongs to a class of medicines called immunomodulatory agents. It works by helping the bone marrow to produce normal blood cells and by killing abnormal cells in the bone marrow.

What are the chances of patients with myelodysplastic syndromes being cured?

As discussed above, the prognosis of patients affected by myelodysplastic syndromes varies depending on their type and grade (see types of MDS). However, the only treatment to cure this disease is a bone marrow transplantation which is reserved for young patients with high-risk MDS (IPSS-R very high, high and most of the intermediate ones especially with a score above 3.4, poor prognostic molecular factors). It is also considered in young patients with high transfusion dependency who do not respond to previous therapies.

Links of interest concerning medical issues relating to myelodysplastic syndromes

- Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in adults. American Cancer Society.

- Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Treatment. National Cancer Institute

- Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Leukemia & Lymphoma Society

- Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Bloodwise UK

Links of interest on other topics related to myelodysplastic syndromes

TESTIMONIAL MATERIALS

You can order the booklets in paper format for free delivery in Spain by e-mail: imparables@fcarreras.es

BONE MARROW TRANSPLANT

- Bone Marrow Transplant Guide. Josep Carreras Foundation (content in Spanish)

- What is HLA and how does it work? Josep Carreras Foundation (content in Spanish)

- Graft-versus-Host Disease. Josep Carreras Foundation (content in Spanish)

- History of Bone Marrow Transplantation. Josep Carreras Foundation (content in Spanish)

- How is the search for an anonymous donor conducted? Josep Carreras Foundation (content in Spanish)

FOOD

- How to maintain a healthy diet during treatment? Josep Carreras Foundation (content in Spanish)

- Nutrition guide. Leukemia & Lymphoma Society

OTHER

- Ideas on what to take with me to the isolation chamber. Josep Carreras Leukaemia Foundation (content in Spanish)

- Travel tips for people with cancer. Josep Carreras Leukaemia Foundation (content in Spanish)

- Physiotherapy manual for haematological and transplant patients. Josep Carreras Leukaemia Foundation (content in Spanish)

- Prevention and treatment of oral mucositis. Josep Carreras Leukaemia Foundation (content in Spanish)

- Oral hygiene in oncohaematological patients. Josep Carreras Leukaemia Foundation (content in Spanish)

- Fertility manual: Suffering from blood cancer and becoming a parent. Josep Carreras Leukaemia Foundation (content in Spanish)

- Skin care in the oncohaematological patient. Josep Carreras Leukaemia Foundation (content in Spanish)

- Aesthetic Oncology Manual. Josep Carreras Leukaemia Foundation (content in Spanish)

- Leukaemia and sexuality. Josep Carreras Leukaemia Foundation (content in Spanish)

- 7 ways to wear a scarf. Josep Carreras Leukaemia Foundation (content in Spanish)

Links of interest: local/provincial or state entities that can provide you with resources and services specialised in leukaemia or cancer patients:

In Spain there is a large network of associations for haematological cancer patients that, in many cases, can inform you, advise you and even carry out certain procedures. These are the contacts of some of them by Autonomous Communities:

All these organisations are external to the Josep Carreras Foundation.

STATE

- CEMMP (Comunidad Española de Pacientes de Mieloma Múltiple)

- AEAL (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA DE AFECTADOS POR LINFOMA, MIELOMA y LEUCEMIA)

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present is the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact with the nearest branch or call 900 100 036 (24h).

- AELCLES (Agrupación Española contra la Leucemia y Enfermedades de la Sangre)

- Josep Carreras Leukaemia Foundation

- FUNDACIÓN SANDRA IBARRA

- GEPAC (GRUPO ESPAÑOL DE PACIENTES CON CÁNCER)

- MPN España (Asociación de Afectados Por Neoplasias Mieloproliferativas Crónicas)

ANDALUCÍA

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present is the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

- ALUSVI (ASOCIACIÓN LUCHA Y SONRÍE POR LA VIDA). Sevilla

- APOLEU (ASOCIACIÓN DE APOYO A PACIENTES Y FAMILIARES DE LEUCEMIA). Cádiz

ARAGÓN

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present is the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

- ASPHER (ASOCIACIÓN DE PACIENTES DE ENFERMEDADES HEMATOLÓGICAS RARAS DE ARAGÓN)

- DONA MÉDULA ARAGÓN

ASTURIAS

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present is the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

- ASTHEHA (ASOCIACIÓN DE TRASPLANTADOS HEMATOPOYÉTICOS Y ENFERMOS HEMATOLÓGICOS DE ASTURIAS)

CANTABRIA

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present is the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

CASTILLA LA MANCHA

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present is the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

CASTILLA LEÓN

- ABACES (ASOCIACIÓN BERCIANA DE AYUDA CONTRA LAS ENFERMEDADES DE LA SANGRE)

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present is the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

- ALCLES (ASOCIACIÓN LEONESA CON LAS ENFERMEDADES DE LA SANGRE). León.

- ASCOL (ASOCIACIÓN CONTRA LA LEUCEMIA Y ENFERMEDADES DE LA SANGRE). Salamanca.

CATALUÑA

- ASSOCIACIÓ FÈNIX. Solsona

- FECEC (FEDERACIÓ CATALANA D’ENTITATS CONTRA EL CÁNCER

- FUNDACIÓ KÁLIDA. Barcelona

- FUNDACIÓ ROSES CONTRA EL CÀNCER. Roses

- LLIGA CONTRA EL CÀNCER COMARQUES DE TARRAGONA I TERRES DE L’EBRE. Tarragona

- MielomaCAT

- ONCOLLIGA BARCELONA. Barcelona

- ONCOLLIGA GIRONA. Girona

- ONCOLLIGA COMARQUES DE LLEIDA. Lleida

- ONCOVALLÈS. Vallès Oriental

- OSONA CONTRA EL CÀNCER. Osona

- SUPORT I COMPANYIA. Barcelona

- VILASSAR DE DALT CONTRA EL CÀNCER. Vilassar de Dalt

VALENCIAN COMMUNITY

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present is the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

- ASLEUVAL (ASOCIACIÓN DE PACIENTES DE LEUCEMIA, LINFOMA, MIELOMA Y OTRAS ENFERMEDADES DE LA SANGRE DE VALENCIA)

EXTREMADURA

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present is the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

- AFAL (AYUDA A FAMILIAS AFECTADAS DE LEUCEMIAS, LINFOMAS; MIELOMAS Y APLASIAS)

- AOEX (ASOCIACIÓN ONCOLÓGICA EXTREMEÑA)

GALICIA

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present is the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

- ASOTRAME (ASOCIACIÓN GALLEGA DE AFECTADOS POR TRASPLANTES MEDULARES)

BALEARIC ISLANDS

- ADAA (ASSOCIACIÓ D’AJUDA A L’ACOMPANYAMENT DEL MALALT DE LES ILLES BALEARS)

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present is the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

CANARY ISLANDS

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present is the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

- AFOL (ASOCIACIÓN DE FAMILIAS ONCOHEMATOLÓGICAS DE LANZAROTE)

- FUNDACIÓN ALEJANDRO DA SILVA

LA RIOJA

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present is the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

MADRID

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present is the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

- AEAL (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA DE LEUCEMIA Y LINFOMA)

- CRIS CONTRA EL CÁNCER

- FUNDACIÓN LEUCEMIA Y LINFOMA

MURCIA

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present is the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

NAVARRA

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present is the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

BASQUE COUNTRY

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present is the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

- PAUSOZ-PAUSO. Bilbao

AUTONOMOUS CITIES OF CEUTA AND MELILLA

- AECC CEUTA (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER)

- AECC MELILLA (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER)

Support and assistance

We also invite you to follow us through our main social media (Facebook, Twitter and Instagram) where we often share testimonies of overcoming this disease.

If you live in Spain, you can also contact us by sending an e-mail to imparables@fcarreras.es so that we can help you get in touch with other people who have overcome this disease.

* In accordance with Law 34/2002 on Information Society Services and Electronic Commerce (LSSICE), the Josep Carreras Leukemia Foundation informs that all medical information available on www.fcarreras.org has been reviewed and accredited by Dr. Enric Carreras Pons, Member No. 9438, Barcelona, Doctor in Medicine and Surgery, Specialist in Internal Medicine, Specialist in Hematology and Hemotherapy and Senior Consultant of the Foundation; and by Dr. Rocío Parody Porras, Member No. 35205, Barcelona, Doctor in Medicine and Surgery, Specialist in Hematology and Hemotherapy and attached to the Medical Directorate of the Registry of Bone Marrow Donors (REDMO) of the Foundation).

Become a member of the cure for leukaemia!