Multiple myeloma

The information provided on www.fcarreras.org is intended to support, not replace, the relationship that exists between patients/visitors to this website and their physician.

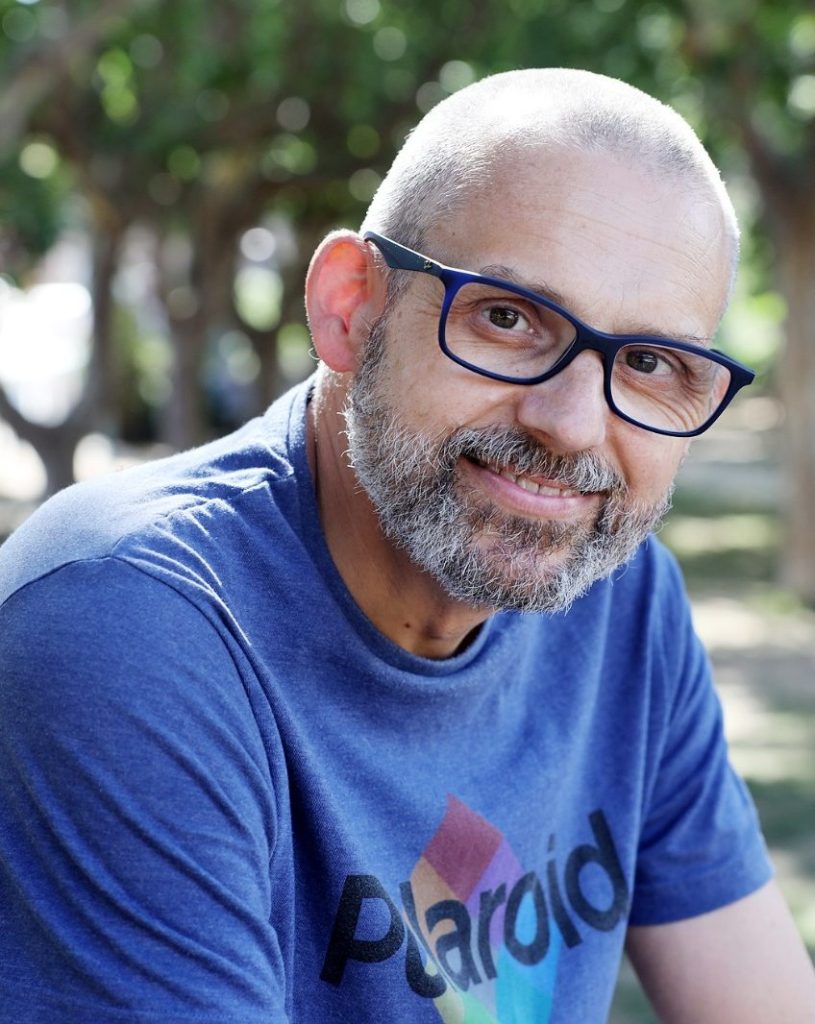

Santi, 52 years old

Multiple myeloma.

“In April 2021, I was diagnosed with multiple myeloma after more than a year with persistent anaemia. The diagnosis of an incurable, and therefore chronic, cancer, such as multiple myeloma, is like a jug of ice water that falls on you suddenly. It is difficult to assimilate in your mind all the information you are receiving from doctors.

These are dark days, with anguish, fear, sadness, also anger against everything and everyone, incomprehension, concerns, … The future as we know it until now disappears. It is therefore time to go through the initial treatment (combination of medications for 6/7 months, apheresis and bone marrow auto transplantation). Each phase with different needs and problems. You learn to focus on each stage, on each day, because situations are changing. It is evident that everything together limits your life, both personal and work, and of course, family life. It is therefore time to adapt to this new situation, to reinvent ourselves. I would like to end with a sentence that I really like and that gives me a lot of strength: you don’t know how strong you can be, when being strong is the only option you have.”

Information reviewed by Dr Albert Oriol. Member of the Haematology Service at the Catalan Oncology Institute – Badalona. Researcher at the Josep Carreras Leukaemia Research Institute. Barcelona Medical Association (Co. 26696).

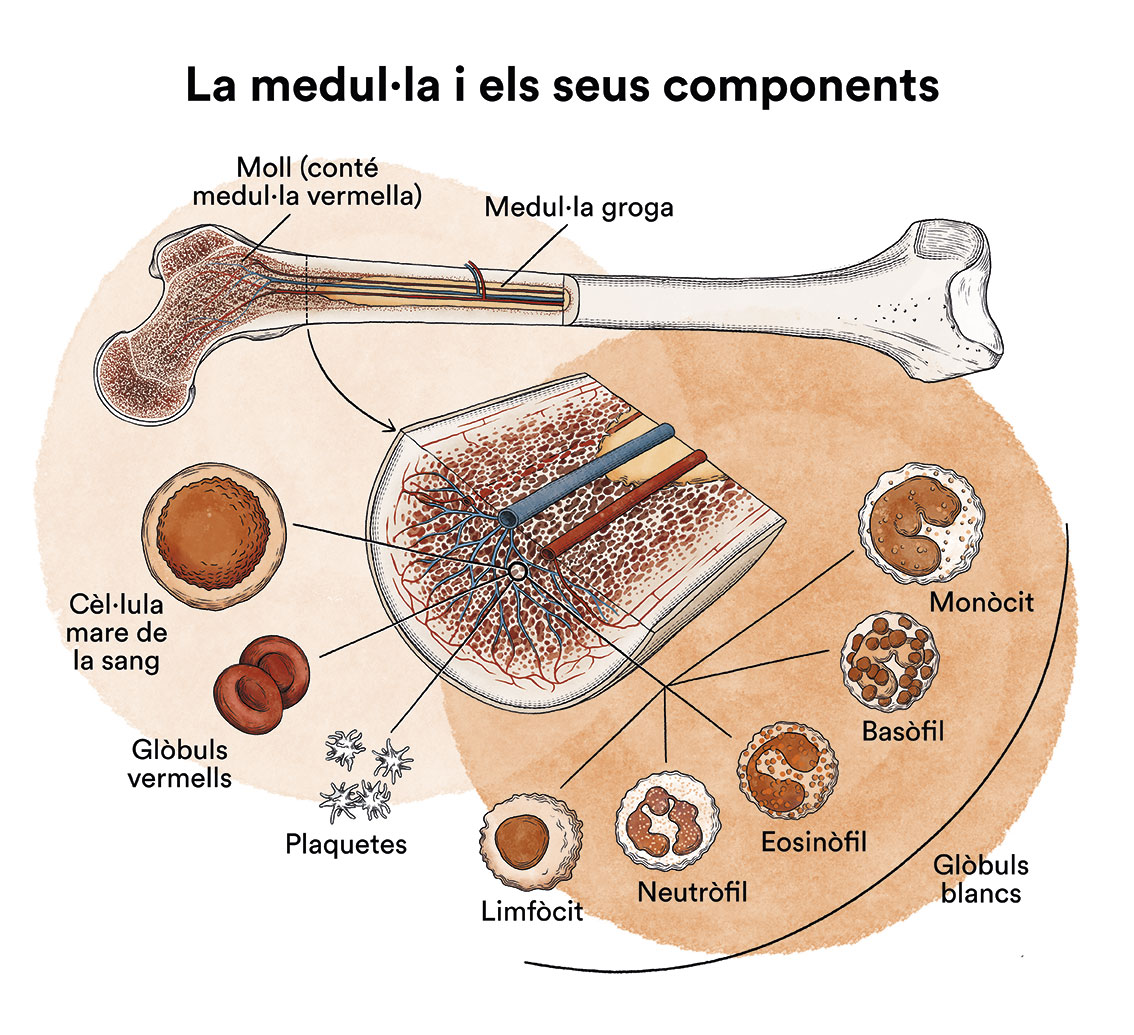

How does bone marrow work and what are the types of blood cells?

Multiple Myeloma (MM) is a type of blood cell cancer that originates in the bone marrow. See section Leukaemia, bone marrow and blood cells.

What is Multiple Myeloma and who does it affect?

Multiple myeloma is a disease of the bone marrow, specifically of the plasma cells, as is the case with all other monoclonal gammopathies.

Normal plasma cells form part of the immune system or body defence system. They are responsible for creating immunoglobulins, which are proteins able to attack germs in the event of an infection. In normal conditions, mature plasma cells only make one type of immunoglobulin and do not reproduce.

Certain genetic alterations can give plasma cells the ability to reproduce and partially occupy bone marrow. This does not always lead to clinical disorders; when this process is asymptomatic, we refer to this as Monoclonal Gammopathy of Unknown Significance (MGUS) or Quiescent Myeloma (QM). People diagnosed with MGUS or QM do not require treatment, but they do need to be monitored periodically, as there is a risk that they may develop active multiple myeloma (MM).

In Europe there are approximately 40 new cases of MM diagnosed per one million people per year. In Spain there are around 3,000 new diagnoses per year. Myeloma occurs specifically in older people, with more than half of patients being diagnosed at age 65 or 70, but it can also affect adults and young people.

What are the causes of multiple myeloma?

There is no known factor that directly causes the onset of multiple myeloma. Factors that increase the risk of other malignancies such as radiations, viruses, tobacco or alcohol do not appear to be linked to this disease. The precursors of plasma cells undergo programmed genetic alterations in the lymph node during their “specialisation” process, and it is possible that errors in these genetic changes are at the root of the development of families of abnormal plasma cells that will settle in the bone marrow later on. To date, no virus or toxic element has been identified as facilitating these erroneous genetic mutations, nor do we know why for some people these alterations lead to the development of a MGUS, which will never progress to a myeloma, whereas for others, the development of a MGUS which then becomes a MM is very quick.

Multiple myeloma is not contagious.

What are the symptoms of multiple myeloma?

The frequency with which we undergo routine blood tests today makes a diagnosis of multiple myeloma (MM) increasingly more common even when it remains asymptomatic, for example, during monitoring undertaken for a MGUS diagnosed by chance.

The most frequent symptom of multiple myeloma (MM) is bone pain, especially in the spinal cord, ribs and hips. MM causes bone lesions known as “lytic lesions”, which are areas of bone that lose their calcium content, leading them to weaken. These lesions are usually very painful and if they are large enough they can also cause the affected bone to fracture, which is perceived as a sudden, intense pain. Sometimes the first symptom of myeloma is vertebral crushing when lifting a weight that is not considered to be particularly heavy, or a fracture following a minor bump.

The second most frequent symptom of multiple myeloma is anaemia. Myeloma cells invade the bone marrow and produce substances that prevent the normal production of red blood cells, resulting in anaemia that generally manifests as tiredness, lack of energy and fatigue as a result of decreasing exertion. Anaemia may also be suspected in the event of pale skin, nails or conjuntiva.

Although pain and anaemia are the two most common symptoms of multiple myeloma, we must keep in mind that pain and tiredness are two very common symptoms of a wide variety of diseases, including viral and bacterial infections or rheumatic diseases. In elderly people, the most frequent cause of bone pain are degenerative disorders, predominantly osteoarthritis, and the most frequent causes of fatigue are cardiac or respiratory problems, all of which are much more frequent than multiple myeloma.

In any case, when faced with pain that is difficult to control with analgesics, or persistent fatigue that increases over time, it is important to undertake a general screening, including a protein determination. In more than 95% of cases of multiple myeloma it is easy to observe anomalous proteins in the blood or urine (known as the monoclonal component or band), which will also help to orientate the diagnosis and to monitor treatment response.

Other symptoms occur less frequently, but are very important as they may require specific treatment and should lead us to quickly suspect multiple myeloma and start the appropriate treatment. The two mains symptoms are hypercalcaemia, an increase of calcium in the blood present in 13% of patients upon diagnosis, or renal insufficiency, present in 19% of patients. Renal failure and hypercalcaemia are detected in basic blood tests. Their clinical manifestations are not particularly specific: lack of appetite, drowsiness, lack of energy or constipation, but they can cause more alarming symptoms such as nausea and vomiting, or drowsiness that can lead to stupor and coma. Urgent medical attention is usually sought in these cases. The problem can be easily identified with a basic emergency blood test. Both renal failure and hypercalcaemia require immediate treatment, even if a MM diagnosis has not yet been made.

It is rare for myeloma to cause a fever, however it is very common for myeloma to be diagnosed at the same time as an infection. In fact, it is important to suspect a general immune disorder in someone who has had more than one serious infection in the space of a few months, especially if there is no known underlying illness to justify this.

Myeloma may also manifest as a hard lump or tumour that generally grows from an area of bone, such as the skull, rib or sternum. When these masses originate in the vertebrae they are not usually visible or palpable, as they tend to grow inward, but they can cause compression of the spinal cord or the nerve roots coming from it. This leads to serious manifestations, such as the loss of leg strength or sensation, or loss of sphincter control (urinary retention). These manifestations are relatively rare, but if they occur, urgent medical attention is required.

MM may also take a long time to be diagnosed, predominantly as the initial symptoms are often not particularly alarming or are easily attributable to other causes (back pain, fatigue, etc…). However, it is important to suspect the presence of myeloma as a result of the presence of pain that cannot be controlled with usual analgesic treatments. An example of this is vertebral crushing. Even if it occurs in an elderly person, a basic study should be undertaken, including at least a basic blood test and radiological imaging. If the blood test shows anaemia, proteins above normal levels, alterations in renal function or an increase in calcium in the blood, MM should always be suspected. MM should also be suspected if X-rays show “lytic lesions” typical of the disease or fractures not caused by prior trauma.

Joan

Multiple myeloma.

“In October 2013, I was admitted to the hospital with severe kidney failure, dehydration, fever,… A few days later I was diagnosed with multiple myeloma. I had never heard that name, but I had heard the word chemo. At that moment, like everyone else, the world came crashing down on me and I cried. In August of the following year, the autotransplant finally arrived, which was a success and here I am… with my after-effects, various infections… but with the desire to live and be grateful for this opportunity given.”

How is multiple myeloma diagnosed?

When suspected, it is relatively straightforward to diagnose multiple myeloma. Two essential testsmust be undertaken:

- A full screening of proteins in blood and urine that enables the monoclonal compound to be correctly identified.

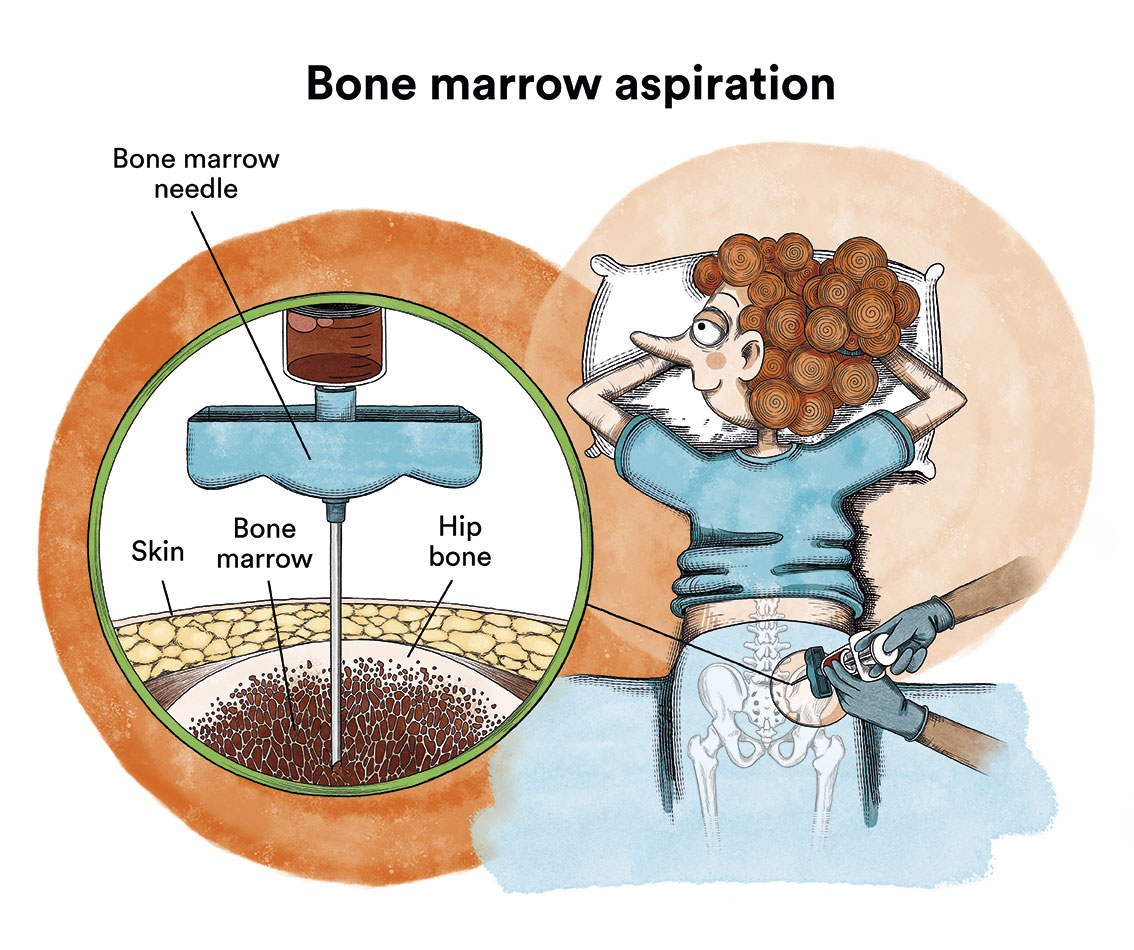

- A myeloma or bone marrow aspiration to confirm the presence of abnormal plasma cells in the bone marrow. This bone marrow aspiration must obtain enough cells to undertake genetic studies (there are genetic alterations with a worse prognosis that should be detected) and flow cytometry studies (to identify characteristics of the myeloma cells that facilitate the monitoring of residual disease following treatment).

It is also important to complete the diagnosis with other key tests to determine the prognosis and focus the therapeutic aim. These consist of imaging tests:

The number and location of bone lesions must be well determined by way of a radiological study of the entire skeleton. Computed Tomography (CT) allows us to see lesions in areas where an X-ray is not sensitive enough. Magnetic Resonance enables us to better assess the spinal cord and is particularly useful in cases where cord compression or myeloma masses (plasmacytomas) are suspected next to the vertebrae. Positron Emission Tomography (PET-CT) can detect lesions in other locations, however it is not always necessary to undertake these tests.

Myeloma is a widespread disease that affects the entire skeleton. Therefore, unlike other cancers, the staging (based on variables such as the amount of monoclonal compound in blood and urine, bone lesions, the presence of anaemia and level of calcium in the blood) does not enable the localised disease to be differentiated from the widespread disease. The measurement of two blood parameters (albumin and beta2-microglobulin) makes it possible to classify myelomas into three stages with different “myeloma quantity” and different prognosis.

How is multiple myeloma treated?

The earliest treatments for myeloma date back to the sixties and were based on a combination of corticosteroids with a group of chemotherapy agents called akylating agents. These medications continue to form a key part of myeloma treatment, but since the end of the last century, the addition of other medications has significantly changed the prognosis of this disease. These new medications pertain predominantly to two families called “immunomodulators” (thalidomide, lenalidomide, pomalidomide) and “proteasome inhibitors” (bortezomib, carfilzomib, ixazomib). They are not considered to be chemotherapeutic agents in the conventional sense of the word, but that does not mean to say that they do not have some undesirable effects.

Generally speaking, none of these medications are used in an isolated manner. Their combined use makes it difficult for multiple myeloma to develop resistance and enables faster symptom control. In general, a more intense and prolonged treatment using a combination of medications is more efficient and the response lasts longer. However, the treatment intensity and duration should be modulated to avoid an excess of toxicity. The individualisation of treatment therefore depends on the patient’s ability to tolerate more or less intensive treatments. Age is therefore a very relevant factor, but not the only one to be taken into consideration.

In relatively young patients (up to 65 or 70 years old) and in an adequate overall condition, the most intensive treatment possible is attempted, including autologous bone marrow progenitor transplantation. The reason for this is that alkylating agents (and in particular the alkylating agent commonly used for myeloma, melphalan) are very toxic to bone marrow cells. Using melphalan in very high doses means increasing its efficacy, but also irreversibly destroying a significant quantity of healthy bone marrow cellularity. Therefore, to administer high doses of melphalan we must first collect bone marrow progenitor cells, administer the high doses of melphalan and then re-infuse healthy cells to enable the blood cells to recover.

In young patients without any other serious health issues, a standard treatment could include a combination of an immunomodulator, a proteasome inhibitor and a corticosteroid for 4-6 cycles (induction therapy), followed by high doses of melphalan with autologous progenitor transplantation and, where possible, adding even more treatment following transplantation (consolidation or maintenance treatments). Therefore, the most frequently used regimens in Spain are VTD (bortezomib, thalidomide, dexamethasone) and VRD (bortezomib, lenalinomide and dexamethasone), VCD (where cyclophosphamide is used instead of an immunomodulator). There is already approval for a quadruple therapy that includes an antibody called daratumumab (targeting CD38, which is a molecule expressed on plasma cells), together with VTD, which will eventually come to replace the previous regimens in patients who are candidates for transplantation and have no contraindications.

In cases where a transplant is not advisable due to excessive toxicity, a three-drug combination is usually employed, which may also include melphalan, although at lower doses, or combinations of only two drugs, always including a proteasome inhibitor, an immunomodulator or both. In any case, the treatment must be adapted to the patient’s fragility in order to avoid excessive toxicity. We can try to maintain the treatments with two drugs or with three drugs in reduced doses or spaced continuously, and thus obtain results similar to those obtained with more intensive treatments.

A combination of two or three medications also tends to be used to treat relapses. When it comes to choosing a treatment it is important to consider the following: the response to previous treatments (previous treatments can be repeated only if they were successful), the toxicity of previous treatments (drugs that have already produced too much toxicity should be avoided), the characteristics of the relapse and the subsequent treatment options in case of failure.

In conclusion, there are various medications indicated for treating multiple myeloma, but it is important to adapt the treatment to each individual, according to their age, characteristics and the nature of their disease.

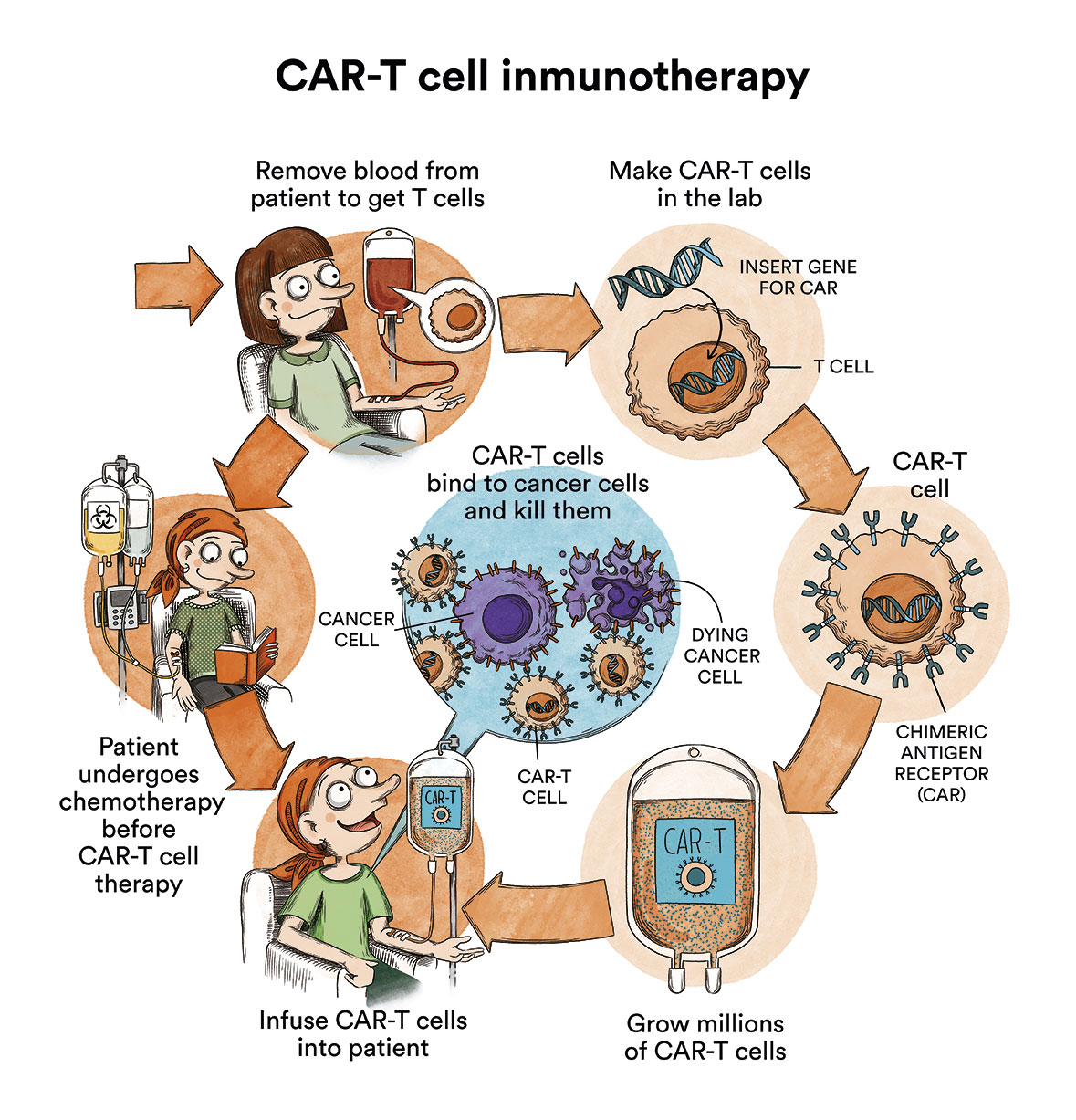

In recent years, CAR-T immunotherapy (content in spanish) has also emerged which, today, may also be of application in selected myeloma patients. Idecabtagene vicleucel (ide-cel, Abecma) and ciltacabtagene autoleucel (cilta-cel, Carvykti) are CAR-T cell therapies that target the BCMA protein, which is present in multiple myeloma cells. These treatments can be used in patients who have already undergone several types of other treatments (usually at least 4) to fight multiple myeloma. Only reference centres authorised to do so can administer them.

Juanma

Multiple Myeloma.

“I was diagnosed with multiple myeloma in 2018. Since then I have undergone six lines of treatment that have failed one after the other, but on the seventh, after a CART cell immunotherapy treatment, I heard for the first time the most wonderful verse in the world : Juanma, the disease is in total remission. There is no trace of tumor cells. The disease is now controlled. When they tell you that you are in total remission it does not mean that you are cured because multiple myeloma is supposed to be incurable at the moment and there may be relapses, but I am more optimistic than ever.”

What is the prognosis for patients with multiple myeloma?

Multiple myeloma is still considered to be an incurable disease. The majority of patients will relapse following the initial treatment for the disease and will require further treatment, which is likely to occur on several occasions. This does not mean to say that the prognosis is very bad. In fact, it is incredibly variable. A small proportion of patients (up to 10%) will have an excellent response to first line treatment and it is possible that they never relapse. We refer to these patients as “functionally cured”, as we can never be sure that MM will not reoccur, even though they have lived 10 or 15 years free of the disease. At the other extreme there are 10-15% of patients who may be resistant to initial treatment or respond initially, but relapse very soon after. In these cases the prognosis is very bad, standing at approximately two years. Between these two extremes, most patients will respond adequately to the initial treatment, their symptoms will disappear or improve significantly following the first weeks of treatment, and they will not be life-threatening in the short or medium term.

Even so, the long-term prognosis is more uncertain, as it will depend on both the frequency and aggressive nature of the relapses. Even with a similar prognosis, patients with less aggressive relapses and a good treatment tolerance can have an excellent quality of life for years, whereas others with aggressive relapses or who do not have good tolerance to different medications can experience aftereffects that reduce it significantly. It is therefore a disease with a very varied prognosis, and although a significant part of the diagnostic study is aimed at trying to predict the type of MM, no test is sufficient in order to give an exact prognosis, neither in terms of time nor in terms of quality of life.

The initial clinical behaviour of MM, and especially the response to the first treatment, will give us significant information regarding the prognosis. In patients with a very lasting response to the first treatment, the response to the second and successive treatments tends to be good, and in these cases we can think of MM as if it were a chronic illness. However, this situation is totally different in patients who, following treatment, relapse very quickly or suddenly and require further treatment immediately. Sudden relapses promote the accumulation of aftereffects (in particular renal insufficiency and bone lesions), and these not only affect quality of life, but they frequently reduce the options of further treatment available.

It is important to anticipate and avoid aftereffects of the disease and the problems related to the toxicity of the treatments by undertaking rigorous monitoring in MM patients, whether they are receiving active treatment or during the time in which they are asymptomatic.

Living with multiple myeloma: diet and care

Treatments for myeloma are toxic and should be monitored and prevented, but they do not stop patients from living an almost normal life. Patients should be particularly aware of two aspects: infections and bone lesions (content in spanish).

Myeloma patients are 10 times more likely to suffer from infections than the unaffected population. This risk is even greater in cases of uncontrolled myeloma, in the initial stages of any treatment and, in particular, in advanced myeloma. Even so, patients with controlled MM who do not require treatment at a given time still have a greater risk of infection than the unaffected population. Respiratory tract infections are the most frequent and, potentially, the most serious. The risk of contracting an infection is not preventable, however, certain basic measures can help to reduce the number of episodes. Taking greater precautions in terms of hygiene, avoiding direct contact with relatives or people with active infections or avoiding crowds as much as possible during flu seasons is recommended. In terms of transmission by contact, frequent hand washing is the most important measure. In special situations (such as hospital waiting rooms) and at times of particular vulnerability (such as after a transplant), wearing a mask is recommended to prevent the transmission of airborne germs. Other simple measures include a balanced and varied diet (vitamin compounds and supplements are not necessary), keeping hydrated, moderate exercise (outdoors is best) and avoiding tobacco and stuffy environments.

Bone lesions caused by MM heal very slowly and bone fragility can be considered permanent, even following successful treatment. It is important to prevent vertebral crushing by avoiding lifting or carrying heavy weights. Moderate exercise strengthens muscles and promotes the recalcification of the bones. However, contact sports or those that require brisk or violent movements are not recommended due to the risk of fractures. Although hypercalcaemia (excess of calcium in the blood) is one of the symptoms of myeloma , calcium rich foods (cheese, dairy) are highly recommended. Treatment for myeloma generally includes medications called biphosphonates, which help the bones to recover by capturing calcium from the bloodstream. Therefore, myeloma patients undergoing treatment with biphosphonates are recommended a calcium rich diet or calcium and vitamin D supplements, as they are much more likely to have low levels of calcium in the blood.

We recommend you research how to maintain a healthy diet during treatment (content in spanish) Look into recommended physical activity and physiotherapy exercises (Physiotherapy manual for onco-haematological patients (content in spanish)) and the EnforMMA programme.

Links of interest concerning medical issues related to multiple myeloma

What Is Multiple Myeloma?. American Cancer Society

Myeloma. Blood Cancer UK

Myeloma. Leukemia & Lymphoma Foundation

Links of interest on other topics related to multiple myeloma

TESTIMONIAL MATERIALS

You can order the booklets in paper format for free delivery in Spain by e-mail: imparables@fcarreras.es

BONE MARROW TRANSPLANT

- Bone Marrow Transplant Guide. Josep Carreras Foundation (content in Spanish)

- What is HLA and how does it work? Josep Carreras Foundation (content in Spanish)

- Graft-versus-Host Disease. Josep Carreras Foundation (content in Spanish)

- History of Bone Marrow Transplantation. Josep Carreras Foundation (content in Spanish)

- How is the search for an anonymous donor conducted? Josep Carreras Foundation (content in Spanish)

FOOD

- How to maintain a healthy diet during treatment? Josep Carreras Foundation (content in Spanish)

- Nutrition guide. Leukemia & Lymphoma Society

OTHER

- Ideas on what to take with me to the isolation chamber. Josep Carreras Leukaemia Foundation (content in Spanish)

- Travel tips for people with cancer. Josep Carreras Leukaemia Foundation (content in Spanish)

- Physiotherapy manual for haematological and transplant patients. Josep Carreras Leukaemia Foundation (content in Spanish)

- Prevention and treatment of oral mucositis. Josep Carreras Leukaemia Foundation (content in Spanish)

- Oral hygiene in oncohaematological patients. Josep Carreras Leukaemia Foundation (content in Spanish)

- Fertility manual: Suffering from blood cancer and becoming a parent. Josep Carreras Leukaemia Foundation (content in Spanish)

- Skin care in the oncohaematological patient. Josep Carreras Leukaemia Foundation (content in Spanish)

- Aesthetic Oncology Manual. Josep Carreras Leukaemia Foundation (content in Spanish)

- Leukaemia and sexuality. Josep Carreras Leukaemia Foundation (content in Spanish)

- 7 ways to wear a scarf. Josep Carreras Leukaemia Foundation (content in Spanish)

Links of interest: local/provincial or state entities that can provide you with resources and services specialised in leukaemia or cancer patients

In Spain there is a large network of associations for haematological cancer patients that, in many cases, can inform you, advise you and even carry out certain procedures. These are the contacts of some of them by Autonomous Communities:

All these organisations are external to the Josep Carreras Foundation.

STATE

- CEMMP (Comunidad Española de Pacientes de Mieloma Múltiple)

- AEAL (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA DE AFECTADOS POR LINFOMA, MIELOMA y LEUCEMIA)

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present in the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact with the nearest branch or call 900 100 036 (24h).

- AELCLES (Agrupación Española contra la Leucemia y Enfermedades de la Sangre)

- Josep Carreras Leukaemia Foundation

- FUNDACIÓN SANDRA IBARRA

- GEPAC (GRUPO ESPAÑOL DE PACIENTES CON CÁNCER)

- MPN España (Asociación de Afectados Por Neoplasias Mieloproliferativas Crónicas)

ANDALUCÍA

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present in the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

- ALUSVI (ASOCIACIÓN LUCHA Y SONRÍE POR LA VIDA). Sevilla

- APOLEU (ASOCIACIÓN DE APOYO A PACIENTES Y FAMILIARES DE LEUCEMIA). Cádiz

ARAGÓN

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present in the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

- ASPHER (ASOCIACIÓN DE PACIENTES DE ENFERMEDADES HEMATOLÓGICAS RARAS DE ARAGÓN)

- DONA MÉDULA ARAGÓN

ASTURIAS

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present in the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

- ASTHEHA (ASOCIACIÓN DE TRASPLANTADOS HEMATOPOYÉTICOS Y ENFERMOS HEMATOLÓGICOS DE ASTURIAS)

CANTABRIA

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present in the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

CASTILLA LA MANCHA

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present in the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

CASTILLA LEÓN

- ABACES (ASOCIACIÓN BERCIANA DE AYUDA CONTRA LAS ENFERMEDADES DE LA SANGRE)

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present in the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

- ALCLES (ASOCIACIÓN LEONESA CON LAS ENFERMEDADES DE LA SANGRE). León.

- ASCOL (ASOCIACIÓN CONTRA LA LEUCEMIA Y ENFERMEDADES DE LA SANGRE). Salamanca.

CATALUÑA

- ASSOCIACIÓ FÈNIX. Solsona

- FECEC (FEDERACIÓ CATALANA D’ENTITATS CONTRA EL CÁNCER

- FUNDACIÓ KÁLIDA. Barcelona

- FUNDACIÓ ROSES CONTRA EL CÀNCER. Roses

- LLIGA CONTRA EL CÀNCER COMARQUES DE TARRAGONA I TERRES DE L’EBRE. Tarragona

- MielomaCAT

- ONCOLLIGA BARCELONA. Barcelona

- ONCOLLIGA GIRONA. Girona

- ONCOLLIGA COMARQUES DE LLEIDA. Lleida

- ONCOVALLÈS. Vallès Oriental

- OSONA CONTRA EL CÀNCER. Osona

- SUPORT I COMPANYIA. Barcelona

- VILASSAR DE DALT CONTRA EL CÀNCER. Vilassar de Dalt

VALENCIAN COMMUNITY

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present in the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

- ASLEUVAL (ASOCIACIÓN DE PACIENTES DE LEUCEMIA, LINFOMA, MIELOMA Y OTRAS ENFERMEDADES DE LA SANGRE DE VALENCIA)

EXTREMADURA

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present in the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

- AFAL (AYUDA A FAMILIAS AFECTADAS DE LEUCEMIAS, LINFOMAS; MIELOMAS Y APLASIAS)

- AOEX (ASOCIACIÓN ONCOLÓGICA EXTREMEÑA)

GALICIA

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present in the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

- ASOTRAME (ASOCIACIÓN GALLEGA DE AFECTADOS POR TRASPLANTES MEDULARES)

BALEARIC ISLANDS

- ADAA (ASSOCIACIÓ D’AJUDA A L’ACOMPANYAMENT DEL MALALT DE LES ILLES BALEARS)

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present in the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

CANARY ISLANDS

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present in the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

- AFOL (ASOCIACIÓN DE FAMILIAS ONCOHEMATOLÓGICAS DE LANZAROTE)

- FUNDACIÓN ALEJANDRO DA SILVA

LA RIOJA

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present in the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

MADRID

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present in the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

- AEAL (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA DE LEUCEMIA Y LINFOMA)

- CRIS CONTRA EL CÁNCER

- FUNDACIÓN LEUCEMIA Y LINFOMA

MURCIA

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present in the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

NAVARRA

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present in the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

BASQUE COUNTRY

- AECC (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER). Present in the different provinces and in many municipalities. Contact the nearest branch.

- PAUSOZ-PAUSO. Bilbao

AUTONOMOUS CITIES OF CEUTA AND MELILLA

- AECC CEUTA (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER)

- AECC MELILLA (ASOCIACIÓN ESPAÑOLA CONTRA EL CÁNCER)

Support and assistance

We also invite you to follow us through our main social media (Facebook, Twitter and Instagram) where we often share testimonies of overcoming this disease.

If you live in Spain, you can also contact us by sending an e-mail to imparables@fcarreras.es so that we can help you get in touch with other people who have overcome this disease.

* In accordance with Law 34/2002 on Information Society Services and Electronic Commerce (LSSICE), the Josep Carreras Leukemia Foundation informs that all medical information available on www.fcarreras.org has been reviewed and accredited by Dr. Enric Carreras Pons, Member No. 9438, Barcelona, Doctor in Medicine and Surgery, Specialist in Internal Medicine, Specialist in Hematology and Hemotherapy and Senior Consultant of the Foundation; and by Dr. Rocío Parody Porras, Member No. 35205, Barcelona, Doctor in Medicine and Surgery, Specialist in Hematology and Hemotherapy and attached to the Medical Directorate of the Registry of Bone Marrow Donors (REDMO) of the Foundation).

Become a member of the cure for leukaemia!